Jeanne Heuving: Some women writers and artists are quite shy or even agoraphobic. Emily Dickinson and Marianne Moore come to mind. Yet as artists occupying public spaces, they are bold. This may be because the public role of artist enables them to side-step typical gender expectations that can be so inhibiting and weakening.

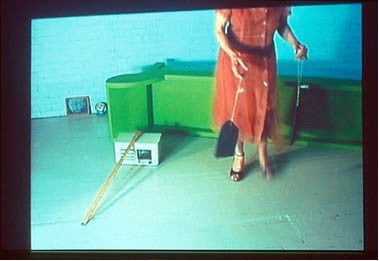

Joan Jonas, Lines in the Sand, 2002, Multimedia Installation, Video Still

Joan Jonas: The convention that you have to behave well makes one shier. One excitement of being a woman artist is, in fact, that you can control your public face more. That’s exactly why I hate descriptions of women artists that begin with: She’s so personal or she’s so eccentric. My work is really something made for the public. I never want it to be described as autobiographical.

Susan Howe: Or yourself to be described as a “woman artist” because it’s a narrower category then the one we hope we occupy, which is simply that we are “artists.” But you touched on a danger zone. I keep saying, I’m a poet, not a scholar. Yet I’m always skipping into scholarship. I can’t let it alone. I force myself into it. Joan, you said you’re a visual artist, but have no training as a dancer; and you’ve also said you’re not a writer. We seem to propel ourselves into these situations where we have to apologize. But you do it. Gilles Deleuze, in “Towards a Minor Literature,” speaks of the artist who, in a foreign country with an adopted language, has to plumb that eccentricity. Out of this situation comes something universal.

JJ: It could be an advantage not to be trained. The roughness is an advantage. One problem with art school is that students are learning all of these things we had to work out for ourselves. A student of mine took courses in literature at Harvard, and it informed his work. Information also comes from outside the art world, especially since art is so inward-looking now. One doesn’t even have to go to art school to get a good art education, but it does give young artists a time and space away from outside pressures. I wasn’t trained in video art or performance. Nobody was in the early 1960s. There was nothing to be trained in, because there was no tradition of video or performance; it was a totally new territory. There were artists working in dance and there were happenings, but it wasn’t a school. When contemporary American artists first started going to Europe, I remember Philip Glass saying, “The Europeans think we’re primitives.” That was the advantage of being American; we were fresh, and the language was fresh.

SH: There’s an innocence (weird as this may sound these days) to Americans. Someone, writing about T. S. Eliot and Wallace Stevens, said that American poets are tourists. Like an autodidact, the tourist takes one thing here and another there, and goes to see this and that. I go from author to author. You go from country to country. This is very American.

JJ: I was just reading about Donald Ritchie, the chronicler of Japanese culture. He said that being a tourist, you can go and get lost — you forget yourself. I identify with that. To go to a foreign country is like performing in a way; you’re not yourself. Within your own context you play a certain role. When I go to Europe, I sometimes think, you can be someone else, a different person, or dress differently; it’s like performing. When you go to another country, you’re actually in a silent space because you don’t speak the language. You are an observer outside of the culture. That is what makes Chris Marker so appealing; he goes around recording and commenting. He turns it into his own work, something else.

Chris Marker, La Jetee, 1962.

SH: You always have material in stock that you transfer. You take along certain props or a series of props, from performance to performance. To direct sound you yell, sing, blow through tin cones, look through them as if they were a telescope. This is similar to a series poem, where the props are certain words, and it’s a matter of moving the word from section to section. Could you say more about your use of props?

JJ: From the beginning I looked for something material to hold on to. My first inspiration was Jorge Luis Borges’ Labyrinths, where I found the idea for mirrors. I also noticed that dancers look at themselves in the mirrors constantly. I liked to look at myself in the mirror, too. I played with it, though it was a taboo subject at that time. Artists came out against narcissism, but I always like to choose subjects that people react against. I like seeing people glance at themselves in those big dining-room mirrors, and I incorporated this awkwardness into my early performances. The audience could see themselves, but perhaps felt uncomfortable. I like to have that going on in the audience. Everybody looks, but you don’t want others to see you doing it, because nobody likes a narcissist.

Joan Jonas

JH: It’s taboo. Women are supposed to be seen, not see themselves. John Berger, in Ways of Seeing, describes how culturally women are taught to be aware that people are looking at them, but they are never to show they are aware of it. As he writes, “Men act and women appear.” Using mirrors with everyone looking at themselves, you break through these conventions. What other props do you use?

JJ: I have also used the cone. In Funnel (1974), I made paper cones that then led to a cone-like paper set. Later, in Mirage (1976), I had them made out of metal. To me, the form of the cone suggested volcanoes, so I found film footage of volcanoes erupting for the performance. You start with one element, and often end up with another. For example, I went to see Bergman’s film Faithless. I liked the title because it was one word that signified just that, faithless. I asked my students to choose one word for a project. In a way that’s what you need, one word that signifies, that triggers, like the cone.

![]()

![]()

Joan Jonas, Performance, 1974, Funnel 5’Umatic

b/wML/V 1985/43

(see a clip of Funnel)

SH: In one of my poems, I took the archaic word thorow— which used to be the spelling of the word through, and suggested other words like thorough, Thor and throw — as well as, most importantly, being a pun on Thoreau’s name. This triggered a year’s work for me. It was as if that word was as solid as a prop http://wings.buffalo.edu/epc/authors/howe/thorow.html.

JH: The word becomes an iconic or totemic object that connotes. H. D. brings in certain objects into her poetry over and over again — sandals and scarves, snails and butterflies. She creates her own ritualistic objects. In twentieth-century experimental work, I am drawn to the tension between aesthetic enclosure and the refusal of this enclosure. This tension seems very important in Joan’s work, and Susan’s, too. While much avant-garde or experimental work aims in part to divest the art object of its aura as art, it is also investing this divestment with new aesthetic effects. We need ritualistic objects in a contemporary time when so many of our public rituals no longer command belief or respect. These objects might be seen as overly eccentric or chosen in some sense, but they are intended for high impact — to connote and excite. Artists need a certain sense of magnetism or magic in order to motivate themselves, to propel their own artwork. H. D. accrues meaning and power as she invests in the same objects over and over again.

H.D.

Many avant-garde women artists might be seen as acting on their sense of being positioned outside of culture, or what Jacques Lacan refers to as being located “elsewhere.” They are not placed in positions of power within the culture, and so, far more radically, must make not only their art but contexts for their art. That’s why I think one often finds a higher degree of experimentalism in women’s experimental work than in men’s. Iconic objects disrupt symbolic systems. Women artists may be motivated for social reasons to make art, but they bring in significant objects to excite themselves into making art.

![]()

Joan Jonas, Funnel, performance 1974, Walker Art Centre, Minneapolis.

JJ: Essentially, H. D.’s a collector, just as I am a collector of objects and you’re a collector of words. I always thought the activity of putting one object next to another was like making a visual poem. In that regard I’m interested in why you chose Charles S. Peirce as a subject. Was he, and not Roland Barthes, the first person to have a system of symbol and icon?

SH: Yes, he was. Peirce was also a compulsive collector of words. A tireless maker of word-lists, he published hundreds of dictionary definitions. Americans are drawn to European theorists like Barthes, Derrida, Deleuze, Wittgenstein, etc. We pay less attention to American pragmatists like James and Peirce. The grass is always greener on the other side. I reached Peirce’s existential graphs through my interest in Emily Dickinson’s late manuscripts. I felt that his logical graphs were poetry and drawing at the same time they were logic, and that they need to be seen in facsimile rather than transcription. People are already accustomed to approaching William Blake’s manuscripts in that way. I feel that the same editorial approach should be taken to Dickinson and Peirce, and I would like to see some of their manuscripts displayed as art objects in a gallery.

JH: I just stumbled across a translation of The Veneris Perivigilium / The Vigil of Venus,that provided an account of the ritual itself. Joan, it might amaze you to know that in this account mirrors were used in ways very similar to your early work. Pat Willis at the Beinecke Library informed me that this Latin text was significant for H. D. and Pound early in their lives, when they were courting. I was surprised, when I looked it up at the Yale Library, to find some sixty different translations and editions of it. It celebrates the rites of spring as the rites of love, of Venus, sometimes replaced by Isis, another iconic female figure. The Veneris Perivigilium may have set the wheels in motion for H. D.’s Helen in Egypt, written near the end of her life. In John Auslander’s 1930s translation, he gives an account of the ritual that is uncannily like Joan’s early mirror work. He presents it as a rite of initiation in which mirror-bearers carry huge mirrors that reflect the Venus-Isis figure so that her followers see her in a mirror. She in turn also sees them in these mirrors. She was preceded by ladies-in-attendance who bore sacred items from her wardrobe, some playing with combs in devout mimicry of her toilet.

JJ: Those early works were inspired by ritual, ancient and other. My mother was a collector. We enjoyed going to antique stores together, collecting. The Surrealists were also great collectors and liked going to flea markets. In the twentieth-century tradition, collecting took on a different function.

My grandmother went to Egypt with her family in 1910. When I was working on Helen in Egypt, my brother, who must have been psychic, coincidentally gave me for Christmas copies of all the photographs she had made of her trip to Egypt. So I had those photographs, which became my way of representing the real Egypt in this piece. I also often buy something just because I like it, and later I find a way to use it. I began working on Organic Honey in 1971 that was the first time I used objects like the fans and old dolls my grandmother had given me. The object is often the material I first start working with. What’s important is how the material is manipulated in relation to medium and structure. Time is a material, too. When Richard Serra talks about his work, it’s about the material. In that sense, I’m like a sculptor.

SH: What about the dog that you draw obsessively?

JJ: It’s true I’m obsessed. In this way I am like a primitive or outsider artist, because I like to draw the dog’s head over and over. I could draw it endlessly. Maybe this is sick, but I’m going to keep doing it.

SH: That’s like me, endlessly revising a poem. If you could see what it takes — thousands of pieces of paper to get four lines, a total obsession! But that’s the obsessive way I work, and I have to keep doing it. You mentioned that coincidentally your brother gave you some photographs. When a piece is really alive and going well, you give yourself over to coincidence.

Joan Jonas, The Shape, the Scent, the Feel of Things, 2004, Installation View

JJ: Your mind is a computer into which you load certain information. All kinds of things filter in. They take form, and then you finally just let go. I realized that when I did Mirage. I thought of the cone, and then I saw the hopscotch game in the street. Then everything began to fall in place. I agree with you, but it’s not only coincidence; it’s something else. One interesting question concerning Lines in the Sand is how the Trojan War is still so iconic. After September 11th, every day in the newspaper there would be a quote referring to the Trojan War. Is it because it’s the first war the Greeks wrote about, or the way the poet Homer wrote about it?

SH: I think this is the entire twentieth century. There’s a wonderful book by Paul Fussell about how we’re still reacting to World War I — not World War II, not even the Cold War, but World War I. Simone Weil’s The Iliad, or the Poem of Force beautifully shows how terse the Iliad is — savage brutality occurs without any explanation. Language can convey the essence of the violence of war, but only with great difficulty the language of pain. Women have written so well on this — Elaine Scarry’s book The Body in Pain, in particular. War, in this century, ushered in modernism and disrupted classical syntax. The Iliad in particular, unlike many other texts about war, in its brevity and brutality, is very resonant in our lifetime.

In your earlier work, I was surprised to see you worked with the idea of women who wore the burqa. I can’t even look at it. Jesus, Joan, the burqa, what was that!?

JJ: In the 1970s I met an Italian woman who used to go to Afghanistan to buy for her store. She changed her name to Luxor. She had these burqas and I thought they were beautiful. So I bought some, and used them for the performance. Of course, I could never use them now. I did a lecture at Williams College recently and an Egyptian student in the audience asked why I used the burqa. It was a question I was waiting for, and my answer was only that I thought it was beautiful. Later I asked her what she thought, and she told me it was O. K., because I wasn’t trying to play an Afghani woman. But today, I wouldn’t dream of it.

SH: Marcia Hafif was in Iran years ago, where she often wore a burqa because she said it gave her an extraordinary feeling of power. It didn’t matter what she looked like. She wasn’t feeling like a sex-object to men; she wasn’t worried about looking young or old. She was able to go everywhere, and she just felt incredibly free,

JH: So, what did it feel like to put on that burqa?

JJ: It’s like a mask. I use masks to hide my face and to achieve another identity. But you can move inside a burqua and make beautiful shapes. It is definitely an exotic costume and, although I hadn’t read Edward Said’s Orientalism until I started working on this project, I was very attracted to the East and to anything outside of my own culture. The burqa transformed me, which is what I wanted.

SH: You have been consistently interested in Noh theater. Could you digress a little on what it meant to you to see a Noh performance in Japan?

JJ: Going to Japan in 1970 was another transforming experience. It was the first time I had been to the East, and I went during a period when I was trying to find an alternative language, one beyond Minimalism. Noh is a visual dance theater, closer to what I was interested in and something I could identify with. It’s more abstract, and, I learned afterwards, that is also what attracted Antonin Artaud to Eastern theater. It’s not entirely based on text. Since I didn’t understand the language, I wasn’t following the text. Its poetic aspect is what interested W. B. Yeats and Ernest Fenollosa. They liked the subject matter and thought it was like the Irish literary tradition, the belief in ghosts, for example. There’s no psychological drama in it. The players are men (they also represent the women) wearing masks. In Jones Beach Piece, I started clapping wood blocks together. The sound of wood on wood is central to Noh and Kabuki theater. It wasn’t until much later that I read in The Empire of Signs, Barthes’ book on Japan, about his concept of the separation of sound and text from image and action in the theater. The way they use wood to create a displacement between action and sound is very precise. Beneath the formal surface, the expression is very wild.

SH: Would you say an aspect of Noh is its extreme formal rigor, while, at the same time, it creates ritual with an aura that is the opposite of rigidity?

JJ: You’re absolutely right; these two extremes come out of ritual. Every play has been worked on for centuries, to the point whe re the movement is extremely controlled, choreographed, and ritualistic.

SH: And how does the mask work?

JJ: It erases identity. Let me show you my new mask from Mexico, which I wore in the performance I did for Robert Ashley’s opera Celestial Excursions last year. I put on a mask and a movement comes to me right away. When I look in the mirror, I can see what I look like in it. In this case, I move like this tense little brat. Isn’t she something?

SH: She’s awful. I wouldn’t say she’s a little girl. She’s like a ventriloquist’s dummy; they can be terrifying.

JJ: She isn’t nasty, but she’s angry. You can’t always quite see it from a distance. But strange things can happen with masks. I don’t always use masks quite so literally. I like this one because it’s so strange.

JH: Susan, you have said that you are obsessed. That word can be interpreted in so many different ways. But when you use it, it seems as if you are apologizing for or masking more complex responses. What might obsess an artist is in fact something that needs to be corrected or altered. This culture really emphasizes going with the status quo, being comfortable, so that if you choose not to go along with the way things are, you may need to work extra hard. Then you are thought to be obsessed. But isn’t it actually a clarity, an unconscious decision to reject some prior formulation? And then you just keep going at it until you get it right.

SH: Maybe. But in your rejection, you worry you are wrong. I am obsessive-compulsive, so I use it. I go with it, and I think Joan does, too. But there’s always a magic sense that if you don’t correct something, you’ll be punished. So you have to go do it again. It’s involved with a ritualistic behavior, because you are constantly rearranging or taking one prop or one idea and going with it. There’s a law, something driving you, but it isn’t you in control. It’s beyond you. This also involves the idea of placating.

JJ: I was very influenced by Maya Deren. I saw the four hours of unedited footage about Voudoun rituals she shot in Haiti for the first time at Anthology Film Archives in 1976, before they edited it. There was one image of a man making sand paintings over and over again, and I was very moved by it. I’m interested in this question because I don’t fully understand why I do it myself. It has to do with the pleasure of repetition, which is not the same as obsession.

Photo: Werner Mashmann

JH: In watching the video of Joan’s Lines in the Sand and then seeing it again, I realize I get considerable pleasure from that very repetition of seeing something I had seen previously. Then your work itself is often about repetition, repetition with a difference. As Gertrude Stein said, there is no such thing as repetition, just insistence insisting differently with each iteration. In terms of obsession, I can be quite obsessive in very unproductive ways. Yet my obsessiveness also takes me places I wouldn’t have gone without it. It’s not so much that I fear punishment; I want to get it right.

SH: Didn’t you play hopscotch in Mirage years ago? Repetition is used in hopscotch, too. In that game, you draw a numbered grid, throw a stone into the boxes in successive order, and then hop and jump to pick it up, making sure you don’t land on a line. There’s a winner and a loser. There’s something in the game that has ceremonial power and calls for repetition to avoid punishment.

JJ: Yes. Mirage was partly about games. I’m interested in playing children’s games in performance. In that hopscotch game, I jumped in the numbers 1 through 9, beating the floor with a stick each time. A friend in the audience thought it was violent. For me it’s the nature of children’s games.

JH: The Zeitgeist argument is that the world changes and art is the first to respond to this change in a way that alters people’s psyches. So, if you’re an obsessive artist, you’re repeating that which you don’t want to repeat, because, in fact, it’s not quite adaptive. So you’re moving towards a truth or an adaptation into a different modality than the world currently allows. In that sense, obsessive behavior is an attempt to rectify something one can’t quite get at. With artists it is an attempt to move something that is somewhat intractable, because it’s how we usually think or live.

JJ: On a basic level it also has to do with pleasure.

JH: Yes, that’s true too. I’m making it too purposeful. That’s the critic in me.

SH: I’ve been interested in D. W. Winnicott’s idea of the transitional object. Very basically, he points out that parents have no control over what object — toy animal, blanket — the child will choose to need and love. Once chosen, it becomes all-powerful. It is the object that pulls the child away from the parents and into a relation with the outside world. The object assumes a cultic status and has magic power. Later, the child will abandon or brutalize this beloved thing, which may be thrown to the four winds and suddenly have no value. This phenomenon also concerns art. One tends to abandon a work once it is finished, whereas previously, in the process of creating and performing it, it was loved and needed. In ways, Joan, I think you have carried this idea into your work. Do you think of your props as transitional objects?

JH: I like what you said about props and your desire to make them as significant as the performers. You don’t want the props to be subordinated to the people or the drama.

JJ: Yes, because people are material in the same way. But your question, Susan, is difficult because it touches on psychology. I’ve never been able to read Lacan. But from the beginning, transitional objects have been about constructing my identity in the work. It was somewhat of a coincidence, but in the first pieces I went through the mirror stage. The mirror also enables the performer to see herself the way the audience sees her. I thought of myself as schizophrenic, because I was so separated from the world and very shy. The performances gave me an identity, through visual language, that I didn’t have otherwise. That’s one of the reasons I became an artist. I could go out in public, and even if the public didn’t know me, they would know my work. In this way I could communicate. During the making of Organic Honey, my dog, which was part of my imagery and work, chewed up all my props and destroyed them — the valuable fans that belonged to my grandmother, the French knitted doll, all gone. It was very symbolic. When it happened I thought that this was just part of the whole project. So, yes, in a way, they were transitional.

SH: In our student days at the Museum School in Boston, Lacan wasn’t the ultimate authority on mirrors. We didn’t know what a mirror stage or a transitional object was. You still continue to use many of these now loaded objects, like the mirror and the cone, for example.

JJ: That’s true. I am always re-using them. Artists invent the same language over and over again. There is a terrible pressure to always do something new. Now I look back see things that were only partly developed, and I go back and explore them.

SH: This is one of the few advantages of age to look back and see that words like captivity or wilderness were there at the beginning. Recently, I saw something way back in my first book that showed a sign of what was to come, but I didn’t see it at the time. It’s a surprise, and a pleasure, to look back and see that the word captivity or wilderness was there at the beginning. It’s as William James said, “Life is in the transitions.”

JJ: Speaking of words, when you say transition, I think about all of my problematic transitions in performance. Transition is one of the most difficult things — the in-between parts, getting from one section to the next in one work. Transitions can be the most interesting part, but can also be unsuccessful. My solution is to simply move from one thing to another.

SH: The blank space between two poems in a series invites contingencies.

JH: There are two different kinds of transitions. One is that life itself is in the transitions. There’s a movement from A to B that crosses a gap. If you cross the gap, then you are at B. There is nothing to control or direct this transition; it might even be an arbitrary movement from one thing to the next. It is the movement of life itself. Then there are the more mundane transitions, where you need to take the audience to where you’ve already gone. This is a smoothing-out process. They are completely different phenomena. T. S. Eliot said that much of the best part of his poetry just came to him, and he spent all his time making the in-between stuff, which wasn’t nearly as terrific as what just came to him.

SH: He also said that poetry comes down to craftsmanship. A poet learns from what other craftsmen have done. You accomplish it with the pen, the paste, and the scissors.

JH: It’s interesting you say that collage is an old-fashioned term. Collage is actually a very useful term, and I have re-incorporated it into my vocabulary. I used it in a critical book on Marianne Moore I began writing in the mid-1980s, and even then it felt old-fashioned. Quite recently, there has been a series of new writings on collage, which as a term is being recycled. For a while, everyone was preoccupied with Lévi-Strauss’ idea of bricolage, which isn’t quite the same as collage, but similar. Where have we been in the last three decades? What’s being replicated and what’s being overturned?

JJ: Collage relates to film, in which you put totally different things together. It all adds up to one subject eventually, or it could not. It’s about cut-and-paste. People who write about media and the language of the computer now still use these terms. It may be an obsolete word, but it depends on how you use it; it’s just a technique. It’s even harder when you’re moving people around the floor and you have to coordinate their movements with all the other elements. It becomes a four-dimensional unity.

SH: How was it for you when you worked with the Wooster Group on their production of The Three Sisters. Was that a completely different experience? Did it change your work?

JJ: No, it didn’t. Learning text — saying text and being in a play (although the Wooster Group doesn’t like to call them plays) — wasn’t completely different, but it was definitely new. I decided to work with them because they were friends and it was really fun. The first time I played Celia Copplestone (from T. S. Eliot’s The Cocktail Party) was in Nyatt School. Spalding Grey was in it, and we’d laugh hysterically all through the rehearsals. The second time I did it, in Brace-Up, their version of The Three Sisters, was because I thought I should learn to use my voice and text in a different way. I was never acting in the usual sense of the word. Their production was similar to my work, but they carried it further in theater, and they made a wonderful piece. If I had gotten into theater when I was younger, I might have tried to be an actress, because I love it. To be an actress, you have to rehearse and be under somebody else’s direction, and in the long run I don’t have the patience. But it was very interesting, and quite rigorous, to work with Liz LeCompte. We might repeat that sometime in the future.

SH: What do you feel about teaching?

JJ: Teaching keeps me on my toes. The other night at Robert Ashley’s performance, I saw Alvin Lucier, a composer, who lives and teaches at Wesleyan. He is seventy-three and loves teaching, and this inspired me. Students who do inspiring work are my reward, and a few of them become friends. What about you?

SH: I prefer teaching nineteenth-century English and American writers as opposed to workshops. This means I’m usually teaching something where I feel I’m in over my head, because I wasn’t trained as an academic. And half of me says, I have no time to waste — I should be writing poems. Particularly at my age when there isn’t that much time left. On the other hand, having to come up with something that keeps the members of the seminar interested and active, requires improvisation. At its best something electric happens between me and the other members of the group; at its worst, it falls silent and goes dead. For you, what is the difference between teaching and giving a small performance in the loft for friends?

JJ: I rarely perform for my students, though I think I should, and probably will, since they don’t exactly know what a performance is. They often learn by participating in my performances. The source material, mostly documentation, is secondary, whereas a poet can always read them the poems. M. I. T is great, because it is a research institute that encourages faculty to work. On the other hand, it does not have facilities adapted to teaching something like performance art. What I can teach them is my method of constructing a video or performance. In general, I have gotten over my fear of performance by teaching. Self-consciousness disappears, because you have to give constantly.

JH: To bring it back to Helen in Egypt and the politics of war: H. D. actually relived World War I through World War II. Up until the very end of her life, she kept rewriting, in her multiple experimental novels, the story of the group of artists she was a part of around the time of World War I. Helen in Egypt pits love against death through the figure of Helen. This is H. D.’s Can one weigh the thousand ships / against one kiss in the night? Joan, in fact, quotes this in Lines in the Sand. During World War II, H. D. attended séances in London where she met Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding, who was eventually relieved of his post because he was communing with dead pilots. In Helen in Egypt, H. D. is writing about her attraction to this Achilles figure, this man of war, whom she saw as a very noble person and for whom she felt she was a special medium. She saw war very acutely, living in London through two world wars, and through the terrible London blitz.

SH: Norman Holmes Pearson, chairman of the American Studies Department at Yale and executor of H. D.’s estate, knew her from London, where he was stationed as a officer in the O. S. S. (precursor of the C. I. A.), and where Pearson’s friend and fellow officer James Jesus Angleton later worked as the Director of Counterintelligence. Angleton, like Pearson, was a member of Skull and Bones, a secret society at Yale (of which the Bushes were more recent members), and as an undergraduate was editor of Furioso, an avant-garde literary journal which published poets like Stevens, Pound, and Zukofsky. He later may have played a role in Ezra Pound’s being hospitalized rather than being tried for treason. There are endless connections to be made between poets and espionage. Sometimes I wonder whether H. D. in her obsession with Air Marshal Dowding and his dead pilots, may have said too much.

JH: So she was like an oracle.

SH: She went over the edge. Like Cassandra, she saw disaster coming. After finishing Trilogy and The Gift, two of her best books, she had some sort of breakdown. She was drugged, spirited out of London, and incarcerated in a sanatorium in Switzerland for two years.

JH: This is an aspect of her life that I have not studied that carefully. But Pearson was an interesting figure. He was a scholar of the modern poets, and he started American Studies at Yale, which actually began as a rah-rah American thing in response to the Cold War. It has its beginnings in a Cold War mentality, but for a long time has attracted a politically radical group of scholars who are anything but Cold War.

SH: Did you ever see the film based on the book by Jean Le Carré called Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy? In the DVD version there is a long interview where Le Carré discusses Skull and Bones and its connection to espionage. He speaks about Angleton, Pound, America’s paranoia, and the Cold War speculation about the identity of the moles who penetrated Western espionage agencies. After the invasion of Iraq, Le Carré wrote a vituperative attack on American foreign policy that was published in various places. I thought it was one-hundred-percent right on. The relationship here between high art, money and politics is very disturbing.

JJ: Of course, this still continues…

SH: This is a Cold War mentality, which you and I recognize because we grew up during the 1950s.

JH: Thinking about those connections makes Helen in Egypt more interesting, because H. D. creates a powerful female figure in her Helen, over and above those Cold War power surges. Helen in Egypt was written in the early 1950s, although it wasn’t published until 1961. In your work, Joan, do you take up politics quite directly, or do you keep them to the side, separate?

JJ: It’s not so separate; there is awareness of politics in my work, but I don’t make political work. I’m not a political artist. But I have never felt the way I feel now before in my life. When I was editing Lines in the Sand, with every choice I made, I was thinking of the situation in the world. And that situation existed before September 11th. I spend hours reading The New York Review of Books from cover to cover, especially every political article. Many of my friends are very active right now, and are on the Internet everyday. Some feel like stopping art just to work on social issues.

SH: I certainly read Lines in the Sand in terms of September 11th. You probably didn’t realize we were going to be in Iraq when you set it in Las Vegas. The work is weirdly prophetic.

JJ: Of course, the summer we chose the H. D. poem for Documenta XI, war was in the air. I didn’t know we were going into Iraq, but I had understood the connection to September 11th. Right after the event I couldn’t work. Like everyone else I was reading and catching up with history. At the Metropolitan Museum of Art that fall, I saw a wonderful BBC film, Tutankhamen’s Egypt (1972), which contained some early footage on the tomb. There was an excavation scene with properly dressed English men and women watching Egyptian workers digging out these beautiful objects and packing them away. It reminded me of my grandmother’s photographs and Victorian tourism in Egypt.

H. D. was analyzed by Freud in the early 1930s, before the war. A decade or so later, during the war, she wrote about the experience in “Writing on the Walls” (later published in Tribute to Freud, not necessarily a title she herself would have chosen). Her text made me think how we much we are in the 1930s, a period leading to war, now. Another reason I chose that text is because I like the language so much.

SH: We are; I think you’re right. This fall I am teaching Melville’s Moby-Dick — the eternal search for oil. Saddam is Bush’s white whale. If everything is read differently after September 11th, will everything also be made differently? What will artists produce next?

JJ: I do think that you have to think about it. You have to be aware of what’s going on to do anything, but other than that, I have nothing to say. In the middle of the night I turned on the television — this is all about chance — and there was a program about Native Americans, talking about their land. Yesterday, I read about a Russian who first wrote about the biosphere. If the Europeans in the nineteenth-century hadn’t treated Serbia the way they did, Russia might have become a very prosperous country, and this man would have been Prime Minister, in a position for his ideas to be influential. Instead, he was ousted from politics and sent away. He then wrote a book about the biosphere, which was also forgotten, and only re-discovered much later. Just thinking about the biosphere, or Native Americans and their land, you have to wonder about the significance of your own work. It could all disappear [snap], just like that. I think writing is one of the most permanent forms, so you’re both lucky.

SH: Except now the attitude is that if you’re a writer and not working on a computer, you’re over the hill. So the paper is farther away than it was in the bygone typewriter days. I still don’t trust the monitor. Everything can vanish in the blinking of an eye and then what? I don’t believe anything is safe until I see it printed out on paper. I am a poet and you are a performance and visual artist. It’s sometimes difficult to relate the two things, but I notice in review after review, your work is referred to as poetic or poetry.

JJ: You’re right. I started studying art history and sculpture, and then moved on to time-based work, performance and video. But I still referred to other forms in order to work with time. At Columbia University, I took a course with Frederick W. Dupee on American poetry, and was looking at films every other night at Anthology Film Archives. The structures I used came from reading poets like William Carlos Williams, H. D., and Pound’s ABC of Reading as well as from watching early French, Russian, and German films. I was very influenced by the poems, by the idea of poetic structure — the way a poem is put together in relation to the way I put an image together. That’s why I use the word poetic when I talk about my work, because a poem is like a condensed image. Maybe you can’t always see that, but it’s in my mind. The construction of experimental film has a lot to do with poetry.

SH: Film, via the writings of people like Eisenstein, Vertov, and Brakhage (to name only a few) has had an influence on experimental writing. In a performance piece, you use different elements in one space, which is not unlike the way some poets use montage. There’s something similar in your work. When you’re doing a performance, you use separate elements — props, film, yourself — to make a finished piece. The question is, are the separate elements going to connect or not? What is the role of chance?

Joan Jonas, Vertical Roll, 1972

JJ: Surrealism — the idea of putting two different things together — is a big influence. John Cage liberated all of us to take chance — and chances — to connect things. I began using collage and montage, the way experimental film, and early film in general, cut images together to juxtapose them. I started out with very simple things; the mirror pieces were minimal. Then when I later brought in other elements like video, the technology provided a different space in time — one of simultaneity, where more than one idea would be going on at once. The work got even more complex when I started using text, which was another learning process, and not altogether successful every time. Occasionally, it got too complex, too fragmented, too cluttered. But now, after many years of working with video, then installation-performances, I can take more chances putting things together. For instance, I began working on the performance for Lines in the Sand after first making the video installation. I went back into the material I had shot and explored it further, re-editing it, using footage I hadn’t used before, and expanding the length of the sequences. The subject of Lines in the Sand was very interesting for me. I continued to develop it, and presented the performance again in Mexico with new performers. It takes a long time to get a performance to the point where I think it works, and often it doesn’t work quite the way I thought. So, I’m always taking a chance.

JH: You have said that you work intuitively. How do you know that something might work and you’ll take a chance on it, versus when you know it’s not going to work?

JJ: When I know it’s not going to work, I take it out. For instance, in Lines in the Sand, I don’t illustrate things; I represent them. To accomplish this I lay down the text as a sound-track and work against it with images. I just keep trying out different pictures and images until they work.

SH: It is strangely similar to the way I work. It takes me two years to finish one obsession on paper. And even then there’s the question of process over finished work. What about your sense of finishing? When you perform a piece in different places, does it change the piece or is it set in stone?

JJ: It’s not set in stone. When I did the piece in Mexico, I didn’t make major changes. I kept the same script, but had different performers. Victor Muñoz took the place of Henk Visch, who performed in Kassel. Because he himself is a performance artist, he invented other movements of his own, which gave me ideas for yet more. There was a simultaneous translation into Spanish, but I don’t know how it sounded, or how people who know H. D. would feel about it. The performance is affected by the place, the space, and the people performing it. At the market in Mexico City, I found masks, giant funnels, and these great helmets made out of papier-maché that looked Greek, and which are used for a particular ceremony. They provided another little image for the piece. I continuously add little touches like that, but don’t always have time to make big changes, because it takes so much time to rehearse.

SH: What do you feel about final recordings? Do you feel there’s a final version of Organic Honey or The Juniper Tree (1976)?

The Juniper Tree (1976-1978), Installation, solo version, courtesy Yvon Lambert Gallery and the artist. Photo: Queens Museum of Art

JJ: There was a final version of The Juniper Tree, as there is with most of my work. At some point I reach a stage where I say, “This is it; I’ve had it.” But then sometimes I go on. What I’ve been doing lately with pieces like Mirage and Glass Puzzle (1973), is to look again at old material that wasn’t edited or included in the original version. Mirage was only a performance; it was never a separate video piece. I found the original 30-minute film of me drawing on a blackboard (of which I had only used ten minutes in the original performance), and showed it in its entirety. I re-edited other early footage from the 1970s, as a parallel track, and transformed Mirage into an installation. Organic Honey, I wouldn’t touch.

JH: Do you always think that the best version is at the end, right before you get bored with what you are working on, or tired of it, and stop? Or if you’ve recorded it, do you ever go back and decide you prefer an earlier version? Do you ever think, I took that too far; it was better in an earlier version?

JJ: Double Lunar Dogs is a piece I took too far; it lost something because I used too many special effects. I look at some of my work years later and am critical of it, but I wouldn’t go back and re-do it. The last version of Double Lunar Dogs exists as a video. You can’t go back and look up all the original material; technically it’s impossible, and a waste of precious time. Video is always a very expensive and time-consuming process. Some pieces are just weaker than others.

Joan Jonas Double Luna Dogs, 1984.

(see clip)

JH: I instantly was sad when you told me that, because of the choreography in the Mexican performance of Lines in the Sand, you decided not to read some of the H. D. passages. I know you made this decision for technical reasons. But you have a great reading voice; not reading the H. D. passages would greatly alter my relationship to the work. I see you as a stand-in for H. D., as a strong female voice. What I particularly like about your voice is its strength — its contemporaneity and pacing. Helen in Egypt borders on the oracular, and your voice cuts through this. Lines in the Sand has power and immediacy because of your voice and the fact that you are also its maker and performer.

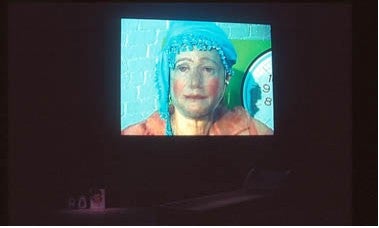

Joan Jonas, Lines In The Sand, 2004 (Installation view). (The Renaissance Society at The University of Chicago)

JJ: I know how important the voice is. When I first started speaking I didn’t like my voice, so I practiced a lot. I would listen to it on tape, and would read a text over and over again until I got it right. When I performed Lines in the Sand at Documenta XI, I intended to have a reader. But, Astrid Klein, who managed the technical aspect of the performance, told me I had to read it. I took her advice. If you are the performer, it’s hard to always be objecti ve about your own performing ability. But I also agree with you: in thinking of myself in relation to this material, I asked, how can I be the performer? I’m not H. D., but another woman in another time. I thought of myself as representing that kind of character. I wasn’t playing either Helen or H. D.; I was playing myself as this particular female poet.

JH: That’s very appropriate, because H. D. is playing at being Helen. Mythical figures can only tell us something about who we are if we take them on, play them. Helen in Egypt is a complex and layered text. I wouldn’t like a work in which an H. D. or the Helen figure was meant to occupy an oracular center, but there is something about having a female figure at the center of this work about war that’s appealing. Although you don’t want to center yourself in the work, it would be very disappointing not to have an echo of H. D. as you. That’s how I would put it — it’s the echo that holds it together.

JJ: I have a catalogue from the exhibition The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting, 1890–1985 at the Los Angeles County Museum, in which there’s a chapter on theosophy I read in relation to H. D. I wanted to find out what she meant by the fourth dimension. The crystal ball in Lines in the Sand refers to H. D.’s involvement with the occult. I touch on it in a superficial way, but I could have done a whole piece on each passage from H. D.’s Tribute to Freud about the fourth dimension and its shape. I had my M. I. T. students work on it, and one physics major did a wonderful piece, with drawings, about length, breadth, thickness, shape, and the fourth dimension.

I know you’re writing a book about H. D., and I’m looking forward to reading it. She is fascinating, but I was overwhelmed. Her life was so complex, and you could spend so much time studying, reading, and trying to understand her, which is what I did not do in this case. I had to stop at a certain point. I didn’t want to get involved in the intricacies of her personal life.

JH: You and Susan have a lot of authority in your voices, which comes from the fact that you know a great deal about what you’re doing. It’s very hard for women to convey authority through their voices without seeming as if they’re mimicking authority. But there’s a matter-of-factness in both your voices that I like a great deal. It’s an attitude and a tone and a way of interacting with the world that is straightforward, and very appropriate to H. D. She was very interested in everyday and ordinary women as they entered into heightened experiences. Joan, your voice is powerful because it’s very self-possessed and unemotional. Yet, there’s color in your voice, without its being dramatic. That’s why it can hold the space of the oracular in a contemporary mode. There’s no mimicry, just you, taking on H. D.

SH: It’s fitting that you picked an H. D. text for Lines in the Sand, and at this particular time in your life. She was in thrall to ritual, deeply involved with séances, telepathy, mirrors, and doubles. The frightening thing was that she was borderline herself. You’ve always had ritual, magic, and incantation in your work, and these can be threatening. Your voice also relates to H. D.’s, which has been recorded reading Helen in Egypt. It is very particular, compelling but removed.

JJ: As a performer, you can’t know how the audience sees you, even if you videotape it. People have said to me that my work seems very personal, and they feel they’re looking in on a private world. In a way, I play off that. After one of my shows, someone asked me whether I purposely make my work eccentric. I don’t think I’m eccentric, but clearly some people do. You find your strength by going into the direction of who you really are. It’s true there are correspondences between many of my interests and those of H. D. But in Lines in the Sand the strongest element is me. I just play myself and use my own images to imagine H. D.

JH: As a critic, I don’t like it when women are cast primarily as personal or eccentric artists. Yet, I must admit that in coming to your and Susan’s work, it is partly through responding to you as individuals, as women, that your work becomes meaningful for me. That is, by engaging the “you” that made the work, I have a more invested or charged relationship to it. Yet ironically, what I really like in your work is how it gives me access to your materials — your icons and texts, your visions. In certain male avant-garde work, although there is little formal emphasis on the artistic self; there is a strong sense of having to attend to, or admire, the creative agency of the piece. When they ask for it, I don’t want to give it. But I do want to lend myself to your work.

SH: For Wallace Stevens the eccentric is the best possible thing.

JH: Marianne Moore says something quite similar, that there is no substitute for “that which is peculiar to the person.”

JJ: I know that. But men have opened up. Matt Mullican and Tony Oursler are two examples of contemporary male artists who do performance-based work and offer themselves to being totally open and vulnerable. They are also both into magic.

SH: In your interview with Joan Simon, you describe the different stages of your early career, which was a trajectory identical to mine: we were the same age, we went to the same art school, and we came to New York at the same time. I was painting and I gave it up. You were sculpting, but gave it up. You went the way I would have wished to go, but didn’t have it to do. I went into a piece of paper, but in my head, I’m moving people around on the stage. I remember Yvonne Rainer and Robert Morris’ performance Waterman Switch (1965) and The Mind is a Muscle (1966), which completely turned me around and changed my feeling about what a woman and an artist could do. In your work you’re drawn to strong women. There was something masculine and feminine about them. Can you expand on the appearance of these strong women, Yvonne Rainer, Lucinda Childs, and Trisha Brown, in your formative years? How do you feel about your peers? And what is the relationship between women and men in the visual arts?

JJ: All these artists had studied with people who were working with Cage. I never actually studied him, but his influence came to me indirectly through them. That’s where this freedom comes from. In the contemporary dance world, there were more women than men, compared to other creative fields, artists like Simone Forti, who studied with Ann Halprin, and Deborah Hay, for example. All those women, along with Steve Paxton, were exploring every-day movement, which gave me a great deal of freedom. Just look at all the different worlds dominated by men: painting, sculpture, writing. But downtown dance was dominated by women, and there was a great deal of interaction and collaboration between the worlds of dance and visual art. That wasn’t my reason for getting involved, but it was probably an unconscious attraction. And I knew I had found my form from the moment I did a performance in front of other people.

Joan Jonas, Lines In The Sand, 2004 (Installation view). (The Renaissance Society at The University of Chicago)

SH: I always had the sense that you were quite shy, so the idea that you loved performance is surprising.

JJ: Oh, I couldn’t even speak to people. Yvonne Rainer and I realized we were both shy, but we both loved to perform. Having an opening in an art gallery is much more painful to me than doing a performance, because in the performance you’re separated, distant from the audience, and shielded by the formality of something you’ve worked out. You can hide behind the work.

JH: Is it just because you have worked it out, or is it also because in a performance you get to be someone else?

JJ: That, too. I never wanted to be Joan Jonas in a performance. I’m always somebody else.

SH: The difference between you and the dancers was that you used words that went beyond dance. When did you start using words in your work?

JJ: In my first performance, dressed in a mirrored costume I recited all the references to mirrors in Borges’ Labyrinths. I recently found A List of the Delusions of the Insane: What They Are Afraid Of, a David Antin poem I recorded to be read for one of my mirror pieces in 1970. Then I didn’t use any words for a while, except a phrase here and there in Organic Honey: “This is my left side, and this is my right side.” When I was commissioned by Suzanne Delahanty to do a children’s piece for the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia in 1976, I chose the Grimm Brothers’ The Juniper Tree. Only when I started working with fairy tales did I get into words in a big way. Text added a complexity which took me a while to work out. To go from the purely visual to the textual was a learning process. As I explored the translation of narrative into visual images, using video for the effects, I sometimes failed.

JH: One thought I have entertained as a critic is how women artists may be the major experimenters of the twentieth century. I am thinking here primarily of the literary field — beginning with Gertrude Stein and up to your work, Susan. The men’s work isn’t as cross-genre or as cross-disciplinary. It doesn’t explore genre as actively because it is more comfortable establishing itself within certain available modes. Or with experimenting with genre within a specific place in the culture set aside for this kind of experimentation. When I teach Susan’s work, a question I often ask is, why isn’t this work being taught in a history department as well as in a literature department? I could ask similar questions of Joan’s work. Why am I not teaching her work in a literature department? Both of your works cross many disciplinary, genre, and media divides. Both are as interested in connection as in disconnection.

In Lines in the Sand, I was more aware of the connections between its diverse elements and less aware of you, Joan, as an artist juxtaposing these fragments against each other. I felt there was a lot in the work that enabled me to connect the different parts together, although ultimately they remained separate, unassimilable. This is the important thing about collage: the different parts aren’t subordinated to each other. Yet, there’s an invitation toward connection in your work that I don’t always get in other avant-garde work, especially avant-garde work by men.

SH: Increasingly, I have to ground my work in a subject or person. And you do as well, Joan, as in your use of H. D.’s Helen in Egypt or Seamus Heaney’s version of Sweeney Astray. You become another character in order to appear in public. So, it’s less of our self, or it’s not our self. Women tend to be mediums.

JJ: It’s our selves in disguise. Someone once made a joke about Hillary Clinton channeling Eleanor Roosevelt. I’m interested in finding characters like the woman from Volcano Saga, which was based on the Icelandic Laxdaela Saga. I think of myself as a kind of medium for information to pass through.

When I think of your poetry, Susan, I always love how you chose subjects like Peirce, which is similar to the way I work. One of my favorites is your work My Emily Dickinson. From the beginning I referred to texts (I was inspired by Joyce and Borges, for example), and there was content in my work that was not always visible. That may be one reason people see my work as European. I can see the similarity in our use of sources — the fragmentation and the visual elements.

JH: How did you initially come upon H. D’s Helen in Egypt? Was it from your earlier reading of her?

JJ: Twice in my career I called Susan, who has a much broader picture of certain subjects than I do. The first time was when I was commissioned to do the children’s piece. I wanted to work with a fairy tale, so I called Susan and another friend, Karin Kennerly. I distinctly remember that Susan said The Juniper Tree was her son Mark’s favorite fairy tale.

SH: Oh, God! It’s about a devouring mother who kills her children.

JJ: When I did The Juniper Tree in Philadelphia I read Bruno Bettelheim. Mothers came up to me before the performance, worried about their children’s seeing such a violent fairy tale. Luckily, one of them had read Bettelheim. His point was that fairy tales are healing. When children experience them, they know they can go through life and survive. The second time I called Susan was the summer I was asked to do a piece based on an epic poem for Documenta XI. I had already worked with epic poems, but I had to write a proposal very quickly, and she suggested H. D.’s Helen in Egypt. That interested me, because according to Robert Graves, the Trojan War was really a trade war, and Helen was a phantom. The Greeks fought for an illusion. This seemed relevant to the present. Susan and I also agreed that it would be interesting to work with an American woman poet.

SH: There was method in my madness. I saw not only the epic connection, but also the age connection.

JH: There’s been a lot of interest in Helen in Egypt. It has something of a cult status within certain poetry scenes. People give it a lot of homage, but there’s very little criticism written. It is actually quite a difficult text.

SH: But one of the wonderful moves in your piece is to have transposed it to Las Vegas. That’s intuition.

JJ: I have to give my assistant Jessica Hutchins credit. I knew I couldn’t go to Egypt, and she mentioned Las Vegas, where she goes with her family every year. She told me the new casino named Luxor might interest me. I immediately knew this was the place to go. With the idea of the trade war in mind, Las Vegas seemed right. Las Vegas is the fake that corresponds to my grandmother’s photographs of Egypt — like the real Helen and the phantom.

SH: You picked up on it, and Las Vegas also goes along with your interest in the contemporary complications of time. It hits H. D. in her sixties and her Helen in Egypt, which can be humorless at times. This takes wit and courage.

JJ: In thinking about being a performer, I decided that as I grew older, I was more interested in humor, to offset sentimentality. As an older person you can’t be romantic and sentimental; you have to be honest about yourself. Also, Helen in Egypt is so serious! There has to be irony. Las Vegas was perfect.

Joan Jonas, Lines In The Sand, 2004 (Installation view). (The Renaissance Society at The University of Chicago)

SH: One thing we share in common is that we were born on the cusp of World War II. Childhood imagination then, even if you were an American child, encompassed such a violent world view — barked orders, bombs, swastikas, marching soldiers, newsreel shots of children being torn from their parents, such fear everywhere. It affects your psyche permanently. That aspect of possible danger carries into your mirror performances. In Mirror Piece II (1970), I was one of the people carrying a mirror, and I remember how heavy and how hard the beveled edges felt. There was the constant suggestion that a mirror might shatter or that something would go wrong. That was part of the effect. In Ireland, if you break a mirror it means bad luck. It’s a transgression. Furthermore, it was also a transgressive act to examine yourself naked with a mirror. For you to strip yourself naked on stage was at the time disobedient in terms of your class and your upbringing; Protestants did not do that. In The Juniper Tree there is also danger. How do you connect all of this to the sense of the violence in the work?

JJ: What was interesting to me about the mirror pieces was that the audience was uncomfortable. They sensed the danger. Life experience is not comforting. Even comedy at its best is disturbing. I knew something about that character in The Juniper Tree through my own experience. You’re right about the danger and the violence. I don’t think I’m always conscious of it, but I was definitely into it. I think it’s necessary to be on the edge. What scares me draws me.

SH: There’s always been an edge to your work, the edge of fear of failure. When you turn more to chance and improvisation, the much more central role of the camera and technology the way you do now, there’s another edge. When your process changes and you accept it as part of the work, you take another chance. But the other side of chance is a severe law.

JJ: For what it’s worth, I’m not afraid of failure in that sense. I’m not afraid to expose myself in a way other people might find unacceptable.

Related Links:

To see a video clip of Joan Jonas’ Lines in the Sand: Helen in Egypt go to http://www.thekitchen.org/04S_feb.html and scroll down.

RE: VOIR Video project for clips of work by Jonas in collaboration with Mekas and Warhol http://www.revoir.com/html/waldenprojection.html

For a bibliogrpahy of work by Joan Jonas see: http://www.eai.org/eai/artist.jsp?artistID=408