“Poetics of Inflection: Rosmarie Waldrop and The Reproduction of Profiles”

by Linda Russo

The Field

Would there ever again be ground for walking? I mean, the field of understanding does not extend to lying down. Later, writing would articulate the absence of voice, pictures, the absence of objects, clothes, the absence of body.

— Rosmarie Waldrop, The Reproduction of Profiles (80)

When we speak of a field of position-takings, we are insisting that what can be constituted as a system for the sake of analysis is not the product of a coherence-seeking intention or an objective consensus (even if it proposes unconscious agreement on common principles) but the product and prize of a permanent conflict; or, to put it another way, that the generative, unifying principle of this ‘system’ is the struggle, with all the contradictions it engenders (so that participation in the struggle — which may be indicated objectively by, for example, the attacks that are suffered — can be used as criterion establishing that a work belongs to the field of position-takings and its author to the field of positions).

— Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production (34)

Understanding, Rosmarie Waldrop suggests, is one position to take in the struggle to constitute cultural truths. Lying down (refusing the take a stand, lying in wait) is another, one that confounds the logic of position-taking that unifies a system of cultural production based on outward signs of struggle “with all the contradictions it engenders,” but does not gender. The feminine, Waldrop suggests, can enact a different logic (lying down as taking a position, perhaps as a form of protest) and this logic can effect change (as lying down in a path to divert traffic). Inserting a feminine thinking subject into masculine/universal philosophical discourse, Waldrop takes such a position: in writing through work of Ludwig Wittgenstein, diverting and redirecting a prepositional logic by putting down observations and propositions, not in the form of assertions, but passively, shrouded in doubt, as in the question “Would there ever again be ground for walking?” The question cleverly describes a situation while provoking that situation to change.

Waldrop’s writing is rich with what she refers to as “semantic slidings” that conflate textual and social fields, such as this metaphorical elision between “ground for walking” and “the field of understanding.” One does not understand, Waldrop suggests, by lying down (passively, or by giving in or putting out); but because the field does not “extend” there, lying down may be one means of extending ground (a way to recuperate ground that has been lost, to provide new spaces in which to walk). Waldrop begins to reconceive, while accounting for sexual difference, the spaces and structures we have constructed for the processes of understanding (language, grammar) by making the female body and a female desire for knowledge present. The question “Would there ever again be a ground for walking” invokes equally physical and intellectual desires – the desire to move one’s body as well as the desire to ply one’s (embodied) mind against the impositions of understandings.

Her invocation in the epigraph of absent bodies invites us to think of which bodies manifest their presence — take position — in the field of poetic production, and how. And though Bourdieu field model reveals the social dimension of literary context and points out the constantly constructed “space of positions and the space of position-takings”(30) he can not account, as he claims to do, for the “full reality”(36) of texts, because what his model reveals is only partial: it doesn’t account for sexual difference. Gender is not considered one of the “visible interactions between individuals”(29). The “sexual indifference” (Irigaray 1985, 72) of his theory serves as proof that maleness in cultural production is a primary effect of this field. Gender remains an invisible interaction; and women appear to simply fail to participate in the struggles that constitute the field [1]

But we know that to be untrue. And we might read the work of women poets as revealing gender to be an effect in poetic production: in Joanne Kyger’s and Alice Notley’s explorations of the epic; in Susan Howe’s remantling of space, time and women’s voices; in Lyn Hejinian’s and Waldrop’s rejections of certainty and closure — the list goes on, but the point is that gender is not a “lens” one may as easily choose not to look through, it is a material fact in determining one’s relation to language, knowledge, power. The new forms and language that such poets create suggests that they are aware of some unexamined presuppositions that constitute — and limit — poetry as a means of articulating a relationship to the world. The idea of poetic possibility, of experiment — Bourdieu also refers to the field of production as the field of possibles — relies on the provisionality, the fluidity, of the field’s constitutive rules, and on the introduction of forces that necessitate change. Waldrop’s long-time work as printer, co-editor and co-publisher of Burning Deck has been to apply consistent pressure to conventional understandings of poetry by encouraging and enabling experimentation. And her poetry is a good place for thinking about poetics, bodies, knowledges, experiment and change.

Waldrop’s work addresses “the field of understanding” as such, a field which ascribes limits to our understanding (and from which we create perceptual models like Bourdieu’s). She encourages us to participate in a semantic struggle where language, as a tool of description, is in flux — in The Reproduction of Profiles this is the ‘ordinary language’ that Wittgenstein attempts to describe in the series of language-games that constitute Philosophical Investigations. like Wittgenstein, she enables us to imagine a process of wonder rather than logical certainty and closure. Her work belongs to the field of position-takings. It engenders contradiction and prizes conflict and struggle. We as readers wrestle with potential meanings, engaging with her in a dance of the intellect. Open forms avoid finality; her work is “reader-centered” in the sense that it opens a dialogue that continues because — she cites Jabès — “Only the reader is real”(1991, 36).

And the ‘real’ reader in The Reproduction of Profiles is the female I in a text composed of series of prose passages that engage the knowledge of a masculine ‘you.’ Despite his certainty the I remains in uncertainty, undecided, even capricious in her resistance to clarity — classically feminine traits that disarm a desire to close with logical conclusions. The I explores, tries to understand, thinks, is not certain, believes, learns, wonders, knows but can not articulate, looks, tries to hear, tries to get facts down, hopes, gets confused — to offer a concordance of verbs that occur in the second section of Reproduction, “Inserting the Mirror.” Sentences often open with propositions “If I” and “As if”, and it is in the same spirit — of asking questions rather than looking for conclusion — that we must engage with this text.

Reproduction reveals the struggle for meaning that is constituted through the body and its desires in a confrontation with logical certainty. She takes Olson’s metaphorical sense of the “skin” as “the meeting edge of man and external reality”(Olson, 161) as a site of intersection, interaction, and one-ness between I and world — a figure through which Olson does away with the division between internal reality (logic, the ordering principal) and external reality — and adds her awareness of “libido and language”(1991, 35). She sensualizes the interaction in a way that Olson felt incapable of doing. In “Human Universe” he contrasts this sense of his body to the Mayan “natural law of Flesh,” in which “there is none of that pull-away which, in the States, causes a man for all the years of his life the deepest sort of questioning of the rights of himself to the wild reachings of his own organism”(158). Waldrop, in opening her poetic form to the body and its desires fully claims that right – that is, to let her organisms (and orgasms) “reach” (and also teach) — and, further, gives the “law of Flesh” (and the uncertainty which Olson alludes to) equal footing with the certainty and authority of logic. The sentences in the prose passages that compose Reproduction proceed as they do because desire in its certainties and uncertainties is as persuasive (it mounts an argument) and determining as the certainty of logic. The extent to which the “wild reachings” of desire “open” form to unpredetermined destinations (the path or road is a pervasive image in Waldrop’s work) contrasts sharply to logic’s “impulse to make order and continuity” (1991, 35), as Waldrop has put it. Surely one must first be able to see the value of impulsive logic before one can appreciate the logic of desire. What this amounts to is what I want to refer to as Waldrop’s Poetics of Inflection.

The Field, Inflected

Visibility was poor. The field limited by grammatical rules, the foghorns of language.— Rosmarie Waldrop, The Reproduction of Profiles (68)

profile:

[It profilo, fr. profilare to draw in outline, fr. pro- forward (fr. L) + filare to spin, draw a line, fr. LL, to spin]

Language shapes and so guides perceptions, making them uniform through commonly held rules such as syntax and grammar. But in limiting the field, do they obscure visibility and put us in a fog, or enable clarity through providing focus? This line of questioning impels Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, his attempt to (serially) describe the use of language — to clarify it: description, not explanation, he contends, is the job of philosophy. Waldrop’s poetics of inflection shows that we must reconsider the logic of our own representations, or the “profiles” (images, outlines, data) we construct in language, and, more particularly, in poetry. Her remarkably complex title The Reproduction of Profiles manages to invoke both printed words and images. While “profile” signifies a visual contour, the word also defines a textual “contour,” a form of information based on analysis, data representing individual exhibits, traits or abilities upon which conclusions are drawn — and the visual representation of this in a graph or “a curve.” Here, also, Olson’s notion of the page as “field” is inflected: it is not only visual, but, as in longer works by some of Waldrop’s contemporaries conceptual as well. [2] This accumulation of text in a book-length field of understanding that supercedes the page creates a conceptual field (writ large, Olson would say) so that dominant notions (logics of syntax and semantics) that determine poetry are pushed to its margins. This feminist poetic doesn’t consist of writing “in” or “from” the margins, but of the creation of new margins in a reorganization of significance and insignificance.

“The Road is Everywhere or Stop This Body”

All roads lead, but how does a sentence do it?

— Rosmarie Waldrop, Lawn of Excluded Middle

In posing this question Waldrop suggests that she’s going to subvert the logic of sentences: in comparing the sentence to a road, she suggests her method: a sentence is a material phenomenon. Words don’t merely refer, they do things. Questioning the nature of the sentence is a provocation as well as a challenge: What is the “it” that sentences “do”? Does a sentence state facts that lead us tour conclusions? Does a sentence have a destination? Can’t we then choose whether to follow its lead or not? How is the sentence’s logic of connection (syntax) different from the logic of walking? This vexatious comparison follows the sentence not to its conclusion, which disappears like a road meeting horizon, but dissolves conclusion, creating instead a multitude of conceptual roads to travel.

The series of prose poems in The Reproduction of Profiles — I’ll call them “passages” to emphasize the connections Waldrop makes between writing and traversing [3] — are concerned with the act of perceiving and describing in a language that Waldrop liberally inhabits as Wittgenstein’s, quoting or turning a phrase, misquoting, following of phrase to its logical or illogical conclusions, in order to, as Waldrop has written, “try to subvert the certainty and authority of logic through the body and its desires” by addressing “the closure of the propositional sentence”(HOW(ever) Vol.4.2, n.p.). Inflecting the deductive logic of linearity, her lines lead us elsewhere, outside of logical reasoning, to reveal how these limit our potential to understand ourselves and the world. Each quasi-narrative passage constantly slips from the “setting” that its narrative logic attempts to establish, so that these work against conventions while using them: there is a protagonist (the narrating I), setting (often composed of elements of a landscape: rain, clouds, trees), and linear continuity (suggested often by uneasy proposition and conclusions). They are internal dialogues in which the female I ruminates upon (and perhaps misremembers or misrepresents) the words of her male interlocutor. What she recalls (without sentimentality) are scenes of instruction, and in her articulation of the exchange the authority of his knowledge is put to the test of the authority of her memory, curiosity and desire:

You said once we had a language in which everything was alright, everything would be alright, and your body looked beautiful while a fisherman tied his boat to a post, looping his rope through the metal rings without getting entangled in problems of representation or reflection. (34)

Such slippages are the mode of assemblage in these prose passage, suggesting that we don’t know whether it is language or the misuse of it that shapes experience into coherent, narrative forms. It is this sense that comes through in the fluidity and elasticity of meaning in these poems. She has written about her focus on language in this way: “because the writer, male or female, is only one partner . . . Language, in its full range, is the other” (1998, 611). One senses the joy that goes into inflecting meaning, in never letting the poem rest (which is perhaps why these are prose poems rather than end-stopped; these lines take no “breaks”).

Inflection

[ME inflecten, fr. L inflectere, fr. in- in- + flectere to bend, turn]

1 : the act or result of curving or bending

4 a : the variation or change of form that words undergo to mark distinctions of case, gender, number, tense, person, mood, voice, comparison

Changes in language and in spatial perception are at play in Waldrop’s poetry, which occupies language and its fields of perception in order to consistently provide a new and challenging set of inflections. These play out on the level of syntax (the poetic line or the sentence) which extends from a series of dialogues between the text’s two subjects on the concepts that compose the philosophical system under investigation (Wittgenstein’s), by inserting her “other” point of view (one informed by cultural position as female, as inhabiting a body with particular desires) the female subject proposes a new set of perceptions, a new set of “truths” unforeseen by, and even unaccountable according to, the discourse to which she is addressed.

It’s difficult to choose one poem to read closely — all are rich and seductive in their linguistic textures and suggestions — and even more difficult to follow up on the multitude of inflections. To read one poem in isolation belies the series in which language is constantly recycled, and it’s impossible to convey the effect of reading these poems, a process punctuated by textual déjà vu, the sense that what you have just read was encountered previously, an effect that reinforces an experience of language as phenomenal and material. Upon investigation, however, this sense of re-experience isn’t corroborated. There was no “profile” reproduced, but one sent instead through many inflections. This begs the question of why we expect repetition rather than change.

Within sentences and from sentence to sentence, “that which is the case” changes perpetually, an effect that comes to Waldrop perhaps through her native, highly-inflected language, German, where, as in Latin, word order is much less rigid than it is in English, and where syntax is such that a clause that appears at the close of a sentence can change the meaning of the sentence as a whole. [4] The result of the inflections in Reproduction is a dual perceptual complexity: on the one hand, the sense of a sentence changes (bends or curves, or “slides”) so that its meaning is redirected; we who were “following” the sentence must change our path. On the other hand, ambiguity clouds the relation between perceiving subject and objects perceived. Both kinds of inflection are evident here in the third passage of “Inserting the Mirror”:

Androgynous instinct is one kind of complexity, another

is, for example, a group of men crowding into a bar while their

umbrellas protect them against the neon light falling. How bent

their backs are, I thought. They know it is useless to look up —

as if the dusk could balance both a glass and a horizon — or to

wonder if the verb “to sleep” is active or passive. When a name

has detached itself, its object, ungraspable like everyday life,

spills over. A solution not ready to be taken home, splashing

heat through our bodies and decimal points. (59)

Under the sort of pressure Waldrop’s experiments exert on the linear logic of prose construction, words become variables (rather than absolutes) — and we read them variably. In an apparent contrast here between an abstraction (an instinct) and a phenomenon (a group of men walking into a bar) the latter becomes abstracted as an example of gender instinct as well: a group of men adhering to a gender identity construed through a shared trait — this particular use of umbrellas (which suggests the arbitrariness of gender characteristics!). This gesture is in turn made strange: why do they need umbrellas to protect them against neon? “Inserting the Mirror” begins as an investigation of rain; isn’t it that condition which presupposes the use of these men’s umbrellas? But women, singly or in groups, use umbrellas the same way? But why do we not see women with umbrellas? Because they are included under the umbrella term “man”? Isn’t it obvious that though androgyny — a blending of gender characteristics — is “one kind of complexity,” men with umbrellas is “another” kind of complexity altogether, having nothing to do with gender? (But how can a group of men not have to do with gender?). Grammatical relief is the fact that there is no contrast here — an analysis which relies on categorization — the sentences aren’t “doing” that — but there’s contiguity, the beginning of a series of kinds of complexities. Yet we are lead down the paths of contrast nonetheless. Finally, what’s so complex about this particular male group phenomenon? The complexity lays in the understanding we as readers form, the extent to which language bends and causes uneasiness and uncertainty, and reveals our reliance on the logic that determines and conventionalizes modes of representation for a sense of stability. For while this passage narrates an event, another event is the series of inflections, a chain of associations that stems from this chain of signifiers. Because there are umbrellas we assume it is raining, but we only know for certain that there is neon. The apparent simplicity of a truth like “umbrellas protect one from rain” is revealed to be inadequate as an explanation of what umbrellas “do” and more appropriately a description of what we use them for: Wittgenstein would agree, and with Waldrop would ask, “what do we use language for?”

In these passages and through their strangeness, inflection is an alternate logic of coherence. Through inflection, associations in narrative and images are drawn both from passage to passage (rain, heat) and within them (bar, glass, spill, splashing, solution). There are points of grammatical bending, transitions points, such as the parallelism in the first sentence, the interjection of the I’s thought formulated to include a consistent pronoun reference (“Their backs . . . they know”), the conjunction “or,” the temporal marker “when” — all this staves off an arbitrariness that would suggest this is merely a collection of sentences and not a “poem” — countering such a suggestion is precisely the challenge these “prose poems” accept. Inflection is a means through which Waldrop searches “for the fine line between closure and openness, where there is closure, but not too much, so that [the writing is] still alive”(1991, 36).

Reflection

“Your thoughts, he said, are the reflection of my own.”

Adeimantus’ response to Socrates explanation of why the poet should be

banished from the Republic (Plato’s Republic, Book X)It rained so much that I began to confuse puddles with the life of the mind. Perhaps what I had taken for reflection was only soaking up the world, a cross of sponge and good will through the center of the eye.

— Rosmarie Waldrop, The Reproduction of Profiles (82)

Water, rain, puddles — such images become figures for “the life of the mind” as it is shaped by available forms. The Reproduction of Profiles is one attempt to create a new method of form. As Waldrop’s poetic language bends and shapes perception, it asks us to question the shapes in which we’ve conceived the world, harkening back to the classic philosophic scene — Plato’s cave. This bending and shaping, this keeping thought alive, is a refusal to settle into forms as a prior authority. Her language wriggles away, flirtatious, leading us by our desire to know, taking us “by the hand”: “what any good poet does is listening to the words and letting them take over and take us by the hand, taking us in unforeseen directions, stretching our original ideas, which can always stand to be stretched”(1991, 30).

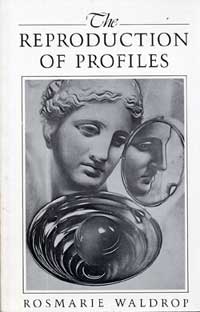

The title The Reproduction of Profiles suggests the method by which inflection replaces reflection as a mode of perception. In the cover image [insert jpeg of cover image], the profile of a classical Greek statue is reproduced, not to effect an identical copy but an alternate image, one reflected slightly “bent,” at a slight angle in the round surface of a hand mirror. Mirroring the left side of the statue’s face effects a second right side view (it is a reproduced profile of both left and right: the left by reflection, the right by mimesis) in this Man Ray photograph where a logic of identification is askew: right and left are not opposites, and right isn’t self-identical. Slight modulations in the physiognomy are discernible; in the mirror image curves of eyelid, nose, or lip suggest a difference of character: where the statue is somewhat wistful, its reflection is more firm and focused. The triangulated compilation of objects invites further speculation: the sense of psychical interiority drawn out in this object/image contrast is echoed in the curvaceous light bulb and light shade — the shade like a womb protecting in its concavity the brain-child — which inflect dually the notion of illumination as sexual and intellectual: a notion that, in 1913, fascinated H.D.. In her feminine poetics Notes on Thought and Vision, H.D. redesigns female reproductive physiology (to combat perhaps a Victorian sensibility that found the womb so problematic and mysterious) as a thought productive physiology: “Should we be able to think with the womb and feel with the brain? . . . The brain and the womb are both centres of consciousness, equally important”(20-21). The intellectual womb: in place of an organ “hidden” from vision, a “love-mind” and a “lens” that contributes to the picture — the perceptions — of the brain. The mind/matter paradigm is subverted.

Bringing the body and its desires to bear on logical propositions, Waldrop’s inflective poetics are a further development of some concepts that provoked H.D., transecting her modernist subversion with a language that contradicts her binaristic logic by sliding over the constitutive conceptual boundaries. Mind and matter are no longer opposed when the boundary between interiority and exteriority — between the I perceiving and the world of objects — is removed. The “I” in these passages is experiential, in the world, refusing to take a position outside of it (from which to establish truths, Wittgenstein asserts). Inflection results in part because there is no subjective certainty in Waldrop’s poetry from which to test whether certain assertions about the truth of reality succeed or fail: there are only perceptual differences. Writing in The Reproduction of Profiles is the act of creating a series of contexts where the challenge of articulating new possibles, new realities, new connections materializes in an otherwise “derealized” world (Bourdieu, 32). They inhabit reality in very much the way Bourdieu hoped to show texts do, as a social reality, a realm of exchanges (and difficulties) between people variously positioned, as her emphatically gendered pair do.

Inserting the Mirror

I tried to understand the mystery of names by staring into the mirror and repeating mine over and over.

— Rosmarie Waldrop, The Reproduction of Profiles (60)

The second section of The Reproduction of Profiles, “Inserting the Mirror,” stresses that inflection, rather than reflection — the mirror does not work on the basis of mimesis — is the text’s modus operandi. What Marjorie Perloff terms “a mock causality,” a form that “determines Waldrop’s syntax [and] marks a notable departure from the syntactic norms of modernist and, for that matter, postmodernist poetic sequences”(209), is also a form of what Luce Irigaray describes as mimicry with a difference, which allows women to speak as women, “to try to recover the place of her exploitation by discourse . . . to resubmit herself . . . in particular to ideas about herself, that are elaborated in/by masculine logic, but so as to make ‘visible,’ by an effect of playful repetition, what was supposed to remain invisible: the cover-up of a possible operation of the feminine in language”(Irigaray 1985, 76). Women are not simply “resorbed” in the act of mimicry. One must “assume the feminine role deliberately” and the artifice this proposes keeps women from being reabsorbed into phallocratic discourse (Irigaray 1985, 76). In Waldrop this is effected by her characteristically feminine role as subordinate, posing questions, tenuous observations and “faulty” propositions. Though these appear naïve, they are never innocent; they are pedagogical, intended to prod, provoke and enliven, and they foreground the uncertainty that lies behind all assertions, the uncertainty that the proposition is meant, if only momentarily, to hide.

The act of repetition — “repeating mine over and over” — will not produce sameness. The image in the mirror is not the equal of the one who gazes, as one’s name does not in any essential way reflect who one is. Words don’t attach to objects (a point Waldrop makes in this text in several places) except by a logic of identification, and even then they only relate or adhere. And, to be sure, that the “I” stares at her reflection is an assumption that the phrase invites but by no means substantiates. This gazing may also reveal all that is “not I” if the line of sight is inflected by the mirror and the gaze is directed toward another point. We must try to understand this sentence, which is itself an assertion of an attempt at understanding, as we find ourselves caught between two images the sentence produces — two truths: the obvious one, reflection, or the less obvious but equally plausible, inflection. One substantiates the law of self-identity (according to Aristotle, A = A): the face of the namer = the reflection of the named; the other asserts that Aristotle’s law of excluded middle (everything is either A or –A) relies entirely on perspective and therefore can’t be universally true. The way words in this phrase miss — fail to positively identify, or provide a representation — is as important as language’s capacity to “hit.” Here we see both sides of the coin at once, neither of which can we take at face value. And yet words don’t lie; as Waldrop challenges in Lawn of Excluded Middle “As if a word should be counted a lie for all its misses”(51).

As “Inserting the Mirror” begins it is clear that language can’t provide an accurate image of the world: “To explore the nature of rain I opened the door because inside the workings of language clear vision is impossible.” This is a simple assertion — one can’t ‘see’ rain in language, it doesn’t happen in language but in the experiential world. The assertion is also rich and suggestive: when one opens the door, is it to step out into the rain? To step out of “the workings of language”? Does one need a “clear vision” of rain — to see it — in order to explore its nature? Does language privilege the sense of sight, only to fail to supply adequate vision? Don’t other senses provide information as well? The next line “You think you see, but are only running your finger through pubic hair” confounds the senses. Perhaps you are using language to “feel” rather than to “see” — to get a sense of, rather than to understand. The sense of touch is very much attuned to contiguities, as when surfaces change (running hands through public hair to approach skin or to approach gender-specific organs), but it is the sense of sight that we privilege as a metaphor for understanding.

The mode of perception that Waldrop constructs is sensual (in both senses of the word). At the skin, feeling and touching are ways of thinking. I don’t feel the rain only; I feel myself get wet, and that is how I know the rain. The utter realism of her language serves to deflate its metaphoric potential, which, as Waldrop shows, obscures rather than clarifies: “I expected the drops to strike my skin like a keyboard. But I only got wet”(57). Is the rain like a keyboard or is the skin? Or both? Or neither — rain does not strike skin like a keyboard. Raindrops make skin wet. Or is the wetness an effect of running fingers through pubic hair? Through this act of inflection, Waldrop explores language’s elasticity, its ability to misrepresent or obscure the world in relation to the persistence of the desiring body in constructing our experience. It is the feminine body, that is, that causes the inflection in phallocratic discourse: inflection is the effect of the language of certainty encountering the materiality of the body and its desires. One can be neither live wholly in language nor give over wholly to the world, but must be amidst both. This is why, perhaps, Waldrop so frequently phrases by means of proposition, an “As if” (disconnecting the “if” from the “then,” cause from result) which is also a challenge, a way to avoid certainty, to keep meaning at play, to imagine a space of possible results, refusing to assign one: “As if one could come into language as into a room”(60). Inflecting Wittgenstein’s descriptive method creates a text that addresses us in so many questions. Despite the fact that they are not posed as questions, our response is invoked, and we are called upon to defend our assumptions, our truths.

Inserting the Mirror II

The phrase “inserting the mirror” corresponds to a particular historical moment which involved inserting an actual mirror to extend one’s view, as a consciousness-raising tactic. The mirror served to allow women to claim themselves as sexual beings while countering the reproduction pornographically of images of their bodies (and thus definitions of female sexual desire) for male consumption. To appropriate (and feminize) the male pornographic gaze was to confound its power, the singularity of its defining potential. It was also to begin to unravel in women’s terms the “mystique” that had determined much of women’s sexual — that is to say, reproductive — lives. This inflection of the phrase “inserting the mirror” concurs with a history of ideas about mind and body. To place Waldrop’s conceptual mirror — which reveals assumptions rather than truths — next to these actual mirrors from a time when the overarching feminist struggle was to render from their own perspective women’s voices and images, is to suggest that though as epistemological methods they differ greatly, they are contiguous projects, having in common the development of female intellection and understanding. Waldrop’s extended poetic project is unabashedly intellectual in this sense. Confronting philosophy, classically the realm of masculine intellection, in a sexualized textual space, Waldrop manages to depart from feminist concerns that are more typically given voice. Her notion of “inserting the mirror” stands in contradiction to the mimetic poetic strategies of feminist “re-vision”; her act of insertion and the elasticity of her language belie the production of static images indicative of the “snapshot” school of feminist poetry. Waldrop’s inflective poetics refocuses “a difference of view” toward a view of differences, one that addresses problems of representation and agency as inherent to the way we use language to shape our world while illustrating how language, as a tool of perception, can be made to bend. Her feminist inflection is thus as powerful as her grammatical and philosophical inflection; all three work together to deform traditional figures of the feminine, to trace a departure, a swerve from well-trod pathways.

Waldrop’s entry into philosophical discourse is through the texts of Wittgenstein, who theorized for the 20th century’s the role of language in constituting the world. Hers is more than an “investigation,” a term that has come to describe the feminist work of many contemporary experimental poets, but a formal instigation. It literalizes the mode of investigation (to hypothesize, question, explore, etc.) with its complex use of the question, which in Waldrop’s text is a “softened,” “feminized” form of assertion, that rather than provoking defensiveness invites contribution. It works in a dialogic mode, bringing the discourse of philosophy into a dialogue which plays out on two levels: between the I of the text who asserts herself through persistent questioning and the you held accountable as the representative of the subject of philosophical discourse, “man”; and between the non-subject (or object) of philosophy, a woman whose body and desires when “inserted” (like the mirror) into philosophical discourse inflect, bend, and, in their redirection, open the primary mode of philosophical discourse, the proposition aimed at establishing certainty. As a dialogue it increases uncertainty by a factor of two. As Irigaray writes of her investigative method in Speculum of the Other Woman, “what is important is to disconcert the staging of representation according to exclusively ‘masculine’ parameters”(Irigaray 1985, 68). Much is uncertain in this text not because Waldrop’s “new proposition” refuses to adhere to the logic of old, but because by establishing her place within philosophical discourse, Waldrop (and the I of the text) begins to deprive “man” of his certain place which she, through “her” silence, had formally constituted for him. But her entry is studied, and her carefully staged question-assertions are an attempt to modify and not simply disrupt logic, to direct it toward other, unforeseen directions: if the synthesis enacted by this dialogic form is productive of conceptual and perceptual change philosophy might begin to produce new truths about subjects and the world. As Irigaray writes, “it is indeed precisely philosophical discourse that we have to challenge, and disrupt, inasmuch as this discourse sets forth the law from all others, inasmuch as it constitutes the discourse on discourse”( Irigaray 1985, 74). Waldrop’s dialogic also ensures that the subjects are not the product of the “sexual indifference” that traditionally defines philosophical discourse. By recounting a heterosexual philosophical dialogue under the authority o the inscribing feminine I, Waldrop demands that philosophy (and poetry) become accountable for sexual difference, to recognize the fact that the world is composed of two distinct subjects whose needs won’t be covered under the umbrella term “man.” This effect, this particular change, would not be possible without the insertion of the female subject into this discourse, not to substantiate (or reflect) the truths established there, but to inflect them.

Works Cited

Bourdieu, Pierre. The Field of Cultural Production. NY: Columbia UP, 1993.

Doolittle, Hilda. Notes on Thought and Vision & The Wise Sappho. San Francisco: City Lights, 1982.

Irigaray, Luce. This Sex Which Is Not One. Trans. Catherine Porter with Carolyn Burke. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1985. 1977.

Olson, Charles. Collected Prose. Berkeley: U of California Press, 1997.

Perloff, Marjorie. Wittgenstein’s Ladder: Poetic Language and the Strangeness of the Ordinary. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1996.

Waldrop, Rosmarie. “Thinking as Follows.” Moving Borders: Three Decades of Innovative Writing by Women. Ed. Mary Margaret Sloan. Jersey City, NJ: Talisman House, 1998. 609-17.

_____. “An Interview with Edward Foster.” Talisman 6 (Spring 1991): 27-39.

_____. Lawn of Excluded Middle. Providence, RI: Tender Buttons, 1993.

_____. The Reproduction of Profiles. New York: New Directions, 1987.

_____. “Working Notes” HOW(ever) 4.2 (Oct.

1987).

Notes

[1] Concepts that are essential to Bourdieu’s theory of avant-garde literary and artistic production have long been put to use in literary criticism, and very recently his “field” has been taken up with particular interest by scholars of poetry at the 2002 Twentieth Century Literature Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, where three speakers (Robert Archambeau, David Kellogg, and Libbie Rifkin) each proposed models of how possibilities are shaped in the field of postmodern poetic production, addressing in particular how notions of the self and factors such as publication and the archive help form poetic identity, how the poet’s relation to these factors determine the field and, subsequently, “position” them “in” the field. The poets who served to people these models were all male.

[2] Lyn Hejinian’s My Life and Hannah Weiner’s Clairvoyant Journals come to mind.

[3] In The Road is Everywhere or Stop This Body, two sorts of traversing as transversion are enacted. First, in the shifting across linebreaks between grammatical subject and object of a line, and second, in the metaphors of circulation — biologic, economic, and geographic — that weave throughout this book.

[4] Waldrop’s frequent use of transitions as a point of inflection to glaze over non-sequitors mimics this mode of semantics: “I was tempted to register doubts as your description progressed, but the wind died down”(52).

Bio: Linda Russo has essays published in The World in Time and Space (Talisman #23-26) and Girls Who Wore Black: Women Writing the Beat Generation (Rutgers, 2002), and the current issue of Jacket <http://jacketmagazine.com/18/index.html>.