Magpie Habits: Alice Duer Miller’s Suffrage Poetry and the Poetics of Quotation

by Mary Chapman

From a conference paper presented at the American Literature Association March 2003

conference on Modernist Poetry, Long Beach, CA

In Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience (1974), Erving Goffman queried the assumption that “in daily life the individual ordinarily speaks for himself, speaks, as it were, in his ‘own’ character. [W]hen one examines speech, especially the informal variety, this traditional view proves inadequate” (512). This same assumption is made in the Western poetic tradition of privileging the lyric, i.e. the form T.S. Eliot said was “the poet speaking to himself or to no one at all”. Nowhere is Goffman’s observation more penetrating than in texts produced during the final decades of the American suffrage campaign (1900-1920), a period in which women writers foregrounded in their work the political and poetic impossibilities of a woman speaking in “her own character”. Denied the vote—the quintessential ideal subjective utterance of a preference, a commitment, a belief—until 1920, women also struggled to speak the self through and within literary forms and traditions established by men. In modernist suffrage literature, women’s voices sound largely through the manipulation of preexisting verbal codes and forms that put them in dialogue with more dominant utterances, for example in drama, conversation and debate, or in reactionary modes like parody, travesty and burlesque.

Taking my cue from Cary Nelson’s observation in Repression and Recovery: Modern American Poetry and the Politics of Cultural Memory that “the literary and social history we promulgated as sufficient in fact suppressed an immense amount of writing of great interest, vitality, subtlety and complexity” (5), this paper examines the suffrage poetry of Alice Duer Miller, a popular poet of tremendous range and skill. Specifically, I am interested in how Miller deploys strategies of quotation and ventriloquism to demonstrate women’s proscribed participation in the public sphere. A novelist, playwright, screenwriter and poet, and one of two female members (with Dorothy Parker) of the fraternal Algonquin Hotel Round Table in the 1920s and 1930s, Miller rose to prominence in 1915 when her serialized Come out of the Kitchen became a best-selling novel. She was a regular contributor of serialized fiction to the Saturday Evening Post, McClure’s, and Scribner’s. By her death in 1942, Miller had published over 25 popular novels. Contemporary reviews described her as “full of the devil” and “a cross between Jane Austen and Henry James” and yet one reviewer acknowledges that it is “difficult for her contemporaries to believe that she is an important artist” (O’Higgins 25): “There is more wit, more perspicacious treatment of well-known human nature, in one of Mrs. Miller’s novelettes than in most writers’ full-length novels” (Overton 206).

Although her fictional output was significant, she was best known in her day for her poetry. The White Cliffs (1940)—a novel in verse depicting a love affair between an American woman and a British soldier during the Great War—sold over 700,000 copies world-wide1, was on the 1941 Publisher’s Weekly bestseller list for non-fiction and earned Miller the Golden Scroll Medal of Honor awarded to the “foremost poet of the nation.” Yet today her work is largely unknown.

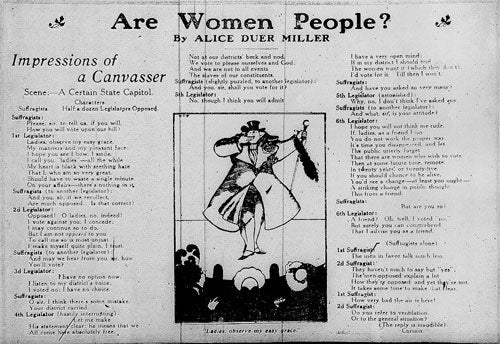

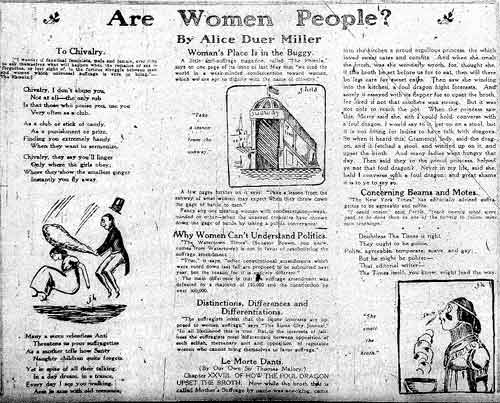

An active feminist—Chair of the Committee on resolutions of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, founder of the Women’s City Club of New York, lifetime member of Greenwich Village’s feminist group Heterodoxy, Trustee of Barnard College—Miller worked tirelessly for the Empire State Suffrage Campaign, giving speeches and contributing a column entitled “Are Women People?” to the Sunday New York Tribune between 1914 and 1917. At that time, the Tribune was a left-wing newspaper which drew its columnists from the Algonquin Round Table and had a Sunday readership of over 100,000 people. Miller’s column began as a edited miscellany of materials relevant to the campaign for women’s suffrage—quotations from anti-suffrage legislators and leaders, cartoons, news of international suffrage campaigns, and statistics—appearing on the Sunday Woman’s Page, but soon it began to incorporate Miller’s satirical and witty verse and to appear on other pages in the Sunday paper, such as the Leisure section and the Magazine. The poems that first appeared in the column were reprinted in suffrage periodicals such as The Woman’s Journal, recited at suffrage rallies, and later collected in two best-selling books published by George H. Doran, a New York publisher of other pro-suffrage materials: Are Women People?: A Book of Rhymes for Suffrage Times (1915) and Women are People (1917). According to contemporary reviews, Miller’s Are Women People? represented the “cleverest, funniest, sharpest collection[s] of satirical verse… since… Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘In This Our World’… the most delightful book of the year so far” (Floyd Dell, Masses. vol vi,. no. 10: July 1915. p. 22.)2.

Miller’s defiant, witty suffrage verse interests me for many reasons, but primarily because it challenges received notions about modernist aesthetics, about the “great divide” between popular and avant-garde that Andreas Huyssen claims is characteristic of discussions of literary modernism, proposing a compromise between poetry that is public and popular, and poetry that is experimental and selective in its audience. Miller’s suffrage verse was published during the decade in which definitions of the function of poetry were “in considerable flux… a contested space”(Harrington 3). Often writing in traditional closed forms, particularly sonnets, quatrains, and couplets, sometimes hailing her addressee as “thee” or “thou”, Miller might initially be read as epitomizing the nineteenth-century genteel poetic. However, at the same time, there is also something politically urgent and incendiary about her suffrage verse, which prompts comparison to newspaper poets such as Anna Louise Strong and propagandist-poets like Arturo Giovannitti, whom Harrington examines in The Social Form of Public Poetry. And, her most surprising work is formally innovative, like the humorous lists presented in “Why Women should not have pockets”, “Why Women should not ride Railway trains”, and “Why children should not go to school” in Are Women People?3

Although most of her verse is not what conventional critics of modernist poetry would call “modern”—indeed, for some readers, Miller’s verse would not even qualify as “poetry”—, it is filled with moments of ventriloquism, quotation, parody, and dialogue, performing what modernist critic Mark Morrison calls the “speech orientation of modern poetry” (Morrison 14). Her poetry anticipates the techniques of what Leonard Diepeveen and Elizabeth Gregory call “the modern quoting poem”, deploying many of the same tactics exhibited in Eliot’s The Waste Land, Pound’s Cantos, and many poems by Marianne Moore, e.e. cummings, Louis Zukofsky and Lorine Niedecker. Published a few years before Eliot experimented with dramatic monologue and “did the police in different voices”, before Pound ventriloquized the River Merchant’s wife and other Asian subjectivities, before Marianne Moore began quoting from “magazines, newspapers, essays, advertisements, travel brochures, [and] government pamphlets” (Slatin 274), Miller took language—its social form and public function—as her primary topic. In her assemblages, particularly her lists and other unusual non-rhyming forms, she creates modernist texts that, like Moore’s, qualify as poetry simply because no other term would really describe them. Poised between poetics, Miller was what one might term a poetic “crosser”, one whose work must be read as “a site for articulating ideological resistance, enunciating alternative subject positions, and politicizing the masses to those positions” (Van Wienen 33-4).

For many modernists, the English language seemed threatened—by the rise of non-English-speaking immigrants, the demise of “standard English”, the potential “contamination” of language by dialect, accent, and slang. However, Miller celebrates rather than fears this multivocality; in fact, enabling conversation (rather than an individual lyric utterance) and collective consensus (rather than individuated positions), particularly through the extension of the franchise to women, is the explicit goal of her suffrage poetry. Miller’s central preoccupation is the operation of language in the public sphere: the relationship between language and subjectivity, between language and collectivity: how language paradoxically both produces and speaks the self—and how, as long as women are denied the vote, the operation of language in the public sphere will be compromised, ineffectual and undemocratic.

Are Women People? and Women are People! are explicitly about the limits and possibilities of speech, particularly female speech, in a culture that does not permit women to actively participate in the public sphere: on the one hand, they depict women’s inability to speak without either being spoken through by other texts that they inadvertently quote and endorse or being spoken for by men, and on the other, they model the ways in which women can articulate their selves by the ironic, parodic, decontextualization and re-framing of these utterances. Quotation and ventriloquism are therefore defined by Miller as both conditions of feminine expression and components of women’s resistance to these conditions. They are both her subject and her method. I would argue that Miller’s production of an implied “speaking female self” through quotation in her suffrage poetry is sympathetic to/anticipates the project of modern quoting poetry more generally but where other modern quoting poems use quotation (particularly from culturally high forms) to establish a relationship between “tradition and the individual talent”, Miller’s quotations from more everyday sources work to model ideal and not-so-ideal operations of language in the public sphere.

Marshall McLuhan asserted that Picasso and Joyce’s modernist methods of collage were inspired by the dialectic of voices assembled in the newspapers (Gregory 22). Alice Duer Miller, more than any other newspaper poet, takes advantage of the dialogic possibilities of a daily print organ, making a collage from the voices of the newspaper—statements from legislators, editorials, letters to the editors, and statistics. Through quotation, or what language theorists would term hypothetical “reported speech”, Miller ventriloquizes common anti-suffrage arguments. Significantly, Miller, like Marianne Moore, quotes not so much from high culture or historical, literary texts as from “common things”, overheard and imagined conversations, prosaic comments from politicians and government agencies, everyday speech from her present moment. The juxtaposition of these “common things” and literary conventions like rhyme, meter, and closed forms defines Miller’s poetic method throughout Are Women People?

Miller’s husband Henry Wise Miller notes in a memoir entitled All Our Lives (1945) that “Alice’s mind was a reservoir of things men had said and done…. without [these quotations] it would be impossible to describe the ways she lived and talked… Alice cut out bits from the papers, … and put them in a special place on the mantelpiece for me to see…. She had no scorn of common things… We had a sort of magpie habit that served as well [as a diary]. Anything that interested us, a clipping, a photograph, a letter was put aside…. We also made a collection of misleading proverbs—aphorisms patently not borne out by experience—and would criticize such dicta as, “The pen is mightier than the sword.”; “Do unto others.”; “Enough is as good as a feast”(34, 138, 163, 170).

The strategy of quotation and ventriloquism deployed in Are Women People? and Women are People! is so insistent, that there are very few places where Miller can be heard to speak “in her own voice” or in the voice of an identifiable “suffragist”. Rather the “voice” or subject position most frequently articulated is the voice of the anti-suffragist. Yet this is not to say that Miller’s positionality is ever unclear. It is established precisely through her summaries of other voices through quotation and ventriloquism. In both of these works of poetry, the voice of the suffragist is what language theorist Janet Giltrow terms a “mobile voice”, one that “accumulate[s] such a dense record of movement—a network of traces, sightings, and sitings—that the speaker[] offer glimpses of [his or her] own subjectivity at each move” (94).

There is something particularly “canny” about Miller’s evasion of the “lyric I”. If the vote as ideal political utterance finds its poetic equivalent in the articulation of the lyric “I”, then through her refusal to assert her own poetic voice Miller stages the limits of feminine poetic selfhood at the same time that she gestures toward an understanding of the vote that goes beyond the individual utterance. She is only ever interested in the vote for what it contributes to a public conversation: for how the individual contributes to a collective.

What does it mean to quote another? to endorse, provide evidence of? to yield power to, to suppress or distort? to assume cultural authority/parity with those quoted? Edward Said notes that “quotation is a constant reminder that writing is a form of displacement. As a rhetorical device, quotation can serve to accommodate, to incorporate, to falsify (when wrongly or even rightly paraphrased), to accumulate, to defend, or to conquer—but always, even when in the form of a passing allusion, it is a reminder that other writing serves to displace present writing” (qu. in Garber 657). Yet for Miller, quotation does not function as Said suggests: to displace present writing. Rather, the unspeaking woman finds speech only through the language that is already made available to her; it does not displace her—it offers her a syntax and vocabulary with which to engage with previous discussions in the public sphere, to be heard/understood. Through quotation, Miller can assert her own unique positionality. As sociolinguist Greg Myers has noted, quoting is also “part of the process by which a collection of people… [can] make itself into a group” (381). Basing his research on the behavior of participants in focus groups, Myers claims reported speech always suggests a shift in frame because it detaches the reported utterance from the reporting speaker—it is an act of thievery, perhaps?—but more importantly, “reported speech [particularly hypothetical reported speech—paraphrase, and so on]—can be seen as part of the process by which a collection of people… makes itself into a group” (381).

The first poem in Are Women People? introduces Miller’s quotational method and reveals the way in which an unspoken position can be articulated through the hypothetical “reported speech” of others. The poem, a dialogue between father and son, appears to function as a kind of democratic catechism except that a child rather than an authority figure poses the questions, and the answers, which conveying orthodox views on the subject, confuse rather than clarify:

FATHER, what is a Legislature? |

Like the volume as a whole, the poem asks questions that can be heard as both fact-finding and rhetorical. The poem’s power rests on two contradictory definitions of “people”: one which excludes them, thereby not permitting them to elect a legislature, and another which includes them, in order to make their tax dollars pay for that legislature. Here the father initially defines people as those who elect the legislature, a group that excludes criminals, lunatics and women—but later includes women in his definition of people, who pay for the legislature. The “mobile voice” located in the interstices between these two premises silently invokes one of the foundational slogans of American democracy—”No taxation without representation”—and quickly makes clear the positionality that the suffrage poet will assume. What is most powerful here is not what is quoted but what is missing; this is characteristic of Miller’s poetic method throughout.

Many poems in the section of Are Women People? that Miller labels “Treacherous Texts” juxtapose actual quotations from anti-suffrage speeches with imagined conversations. “A Consistent Anti to Her Son”, for example, quotes from an anti-suffrage speech in its epigraph: “Look at the hazards, risks and physical dangers that ladies would be exposed to at the polls”, before Miller develops this argument to its ridiculous conclusion through the ventriloquizing of a hypothetical reported speech:

You must not go to the polls, Willie. |

Here paradoxically, an anti-suffragist participates in the political ventriloquism that currently defines the vote, but to very different effects: i.e. if the son “tells” the mother, who will “tell Father” whom to vote for, then the assumption is that Father will supposedly vote on behalf of his disenfranchised relatives. But where the mother’s “ventriloquism” is understood as a passive yielding up of political authority, the Father’s ventriloquism is viewed as definitional exercise of democratic franchise. This revised reading of the performative function of the vote—Miller exposes it not as individuated utterance but as ventriloquising act—is explored elsewhere in her poetry, namely in two separate poems both titled, appropriately, “Representation”. The first, published in Are Women People?, begins with an epigraph quoting Vice-President Marshall’s comment invoking his wife’s opinion—”My wife is against suffrage, and that settles me”. The body of the poem continues, hypothetically, in the voice of the Vice President:

My wife dislikes the income tax, |

Here men’s ventriloquism of the female voice is cast not as appropriation of that voice but as obedience to its authority. Miller exposes the impossibility of this obedience in “Representation” published in the later collection Women are People:

My present wife’s a suffragist and counts on my support, |

It’s unclear to whom this “gentleman” poses his question: who might have the authority to answer his dilemma.

Of course, what all three poems point out is that if men do quote women when they vote, the exclusive granting of the vote to men causes a democratic principle—”one man one vote”—to pervert and compromise itself when the vote ventriloquizes others’ preferences rather than asserts the preferences and opinions of the individual citizen. However, if men don’t quote women exactly when they vote, and don’t therefore represent women, then this democratic mis-representation can only be remedied by enfranchising women. Misquoting men who misquote women then becomes a model for Miller’s method.

In these and other poems in the collection, Miller articulates the suffragist voice not in the lyric “I” but in the accumulation of “mobile voices” produced by the dialogic—by parody, quotation, dialogue, travesty. Together these voices forge a knowing counter-public as Miller’s implied reader hears, in the reported speech of anti-suffragists, Miller’s questioning of authority.

Miller is at her wittiest when she creates “Campaign Material from Both Sides” in the form of absurd lists parodying the materials distributed to campaigners on both sides to provide ammunition for the suffrage debate. Lists like “Why We Oppose Votes for Men”; “Why We Oppose Pockets for Women”; and “Why We Oppose Schools for Children” expose the structural illogic of some of the most frequently used arguments in the anti-suffrage campaign and effectively puts anti-suffrage cant under erasure. For example, “Why We Oppose Women Traveling in Railway Trains” gives 6 reasons:

-

Because traveling in trains is not a natural right.

-

Because our great-grandmothers never asked to travel in trains.

-

Because woman’s place is in the home, not the train.

-

Because it is unnecessary; there is no point reached by a train that cannot be reached by foot.

-

Because it will double the work of conductors, engineers, and brakemen who are already overburdened.

-

Because men smoke and play cards in trains. Is there any reason to believe women will behave better?

Here this phantom “we”—an undefined collective who are united by their unwillingness to allow for change—is as insistent as the lyric “I” is absent.

The only place Miller articles a suffragist positionality, she locates the suffragist voice not in the lyric “I” but rather in the collective, in poems like “An unauthorized interview between The Suffragists & the Statue of Liberty” (published in Women are People) in which a chorus of suffragists ask Liberty “Why you treat your daughters so?” Responding to Emma Lazarus’ 1883 conception of the Statue of Liberty in “The New Colossus” as a “mighty woman” who welcomes “huddled masses yearning to breathe free”, Miller’s statue exhibits a more critical self-consciousness:

I’m not she— |

The interview is “unauthorized”—lacking authority—and yet the collective finds speech precisely in their statement of this unauthorized position. In this poem and throughout Are Women People and its sequel Women are People , Miller forges a knowing counter-public, who can hear in quotation and ventriloquism, a knowing audience who knows the intertext.

* * *

In his memoir Henry Wise Miller described his marriage to Alice as a conversation: “For over forty years we talked and talked; both together when the matter was not important, in half sentences when we were on ground familiar to both, and in lengthy, formal conversation” (122) This portrait of a marriage conveys, in microcosm, the utopian standard against which Miller compares men and women’s interaction in the public sphere. Miller celebrates conversation—whether it is intimate dialogue between men and women in courtship or political debate enabled by the enfranchisement of women—as the corrective to idealizations of [silent] femininity. Miller noted in a radio broadcast she did in the 1930s, that “People love to talk but hate to listen. There’s chatter, monologue but no conversation. A crowd excites us but to no social advantage” (All Our Lives 122). Equal, respectful conversation, particularly conversation between a man and a woman, becomes, in Are Women People? and Women Are People, the grounds upon which the public sphere should be established. Conversation is the “ideal speech situation” (Habermas): at once, the most intimate of exchanges, and, between men and women, representative of more public, necessary exchanges. The two suffrage poetry volumes Miller published are full of productive dialogue largely between men and women where the speakers arrive at new appreciation of each other’s interests and needs through conversation.

In 2004, both Alice Duer Miller and the collection of texts I am calling American suffrage literature are virtually unknown, but they have much to tell us about the cultural work performed by modernist literature in the decade before suffrage was granted: about negotiations around the primacy of the “lyric I” in the tradition that twentieth-century literary criticism, particularly New Criticism, forged, and about the erasure of the voices seeking to explore a collective alternative to a more individuated lyric functioning of language. At this point in my research, I can only hypothesize about the reasons for the exclusion of Alice Duer Miller from the canon by noting that while the proponents of the modern quoting poem utilized the same multivocality Miller explored, their multivocality was ultimately absorbed into a masterly “lyric I” perhaps in the same way that the paradoxes of their poems could be absorbed into a well-wrought urn. Miller’s poetry resists the absorption of multiple voices, holding out for a kind of state subjectivity best represented by what is achieved through dialogue and voting.

Notes

[1] - Encyclopedia Brittanica on-line. (Back to text)

[2] - Biographical information about Alice Duer Miller is drawn from several encyclopedia entries (in Works Cited) under her name, as well as contemporary or recent profiles by O'Higgins, Van Gelder, Schwartz, Overton, Lawton, Anonymous, and the unsigned “A National Industry”. (Back to text)

Reviews of her poetry appeared in The Masses (no. 1; Oct-Nov 1915: 9), TheNew York Times 17 June 1917: 234; The Nation 30 September 1915: 407; The Woman's Journal 19 May 1915: 119; and The Masses July 1915: 28. When Are Women People? was reviewed on the same page as Spoon River Anthology in the [Elyria OH] Evening Telegram 5 Oct 1915, the reviewer observed: "As campaign literature the book is first-class" (4). The White Cliffs, according to the author of “A National Industry", was a sleeper…and had totally unexpected success. The turning point was …when Lynn Fontanne read [it] on an NBC hook-up…repeated two weeks later…One day in December [1940] it sold 1700 copies."

[3] - Poem titles varied slightly between the column and the books. These are the titles of the poems in the column. (Back to text)

Works Cited

“Alice Duer Miller”, Current Biography: Who’s New and Why. Ed. Maxine Block. New York: The H.W. Wilson Co., 1941: 580.

“Alice Duer Miller”, Twentieth-Century Authors: A Biographical Dictionary of Modern Literature. Ed. Stanley J. Kunitz and Howard Haycraft. New York: H.W. Wilson, 1942: 958-9.

“Alice Duer Miller”, Notable American Women 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary. vol. ii. Ed. Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James and Paul Boyer. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971: 538-40.

“Alice Duer Miller”, National Cyclopaedia. vol. A. New York, J. T. White: 378.

“Alice Duer Miller”, The Reader’s Encyclopedia of American Literature. Ed. Max J. Herzberg. New York: Crowell, 1962: 737.

“Alice Duer Miller”, Who’s Who Among North American Authors. Detroit : Gale Research Co., 1976: 1007.

“Alice Duer Miller”, Who’s Who in America. vol. 21, 1940-1941. Ed. Albert Nelson Marquis. Chicago: A.N. Marquis Co., 1940: 1818.

“Alice Duer Miller”, Feminist Companion to Literature in English: Women Writers from the Middle Ages to the Present. Ed. Virginia Blain, Patricia Clements, and Isobel Grundy. New Haven: Yale UP, 1990: 740.

Anonymous. “Alice Duer Miller”, Saturday Evening Post, 16 August 1919.

Dell, Floyd. “Last But Not Least” The Masses. vol vi,. no. 10: July 1915: 22.

Diepeveen, Leonard. Changing Voices: The Modern Quoting Poem. Ann Arbor: U Michigan P, 1993.

Easthope, Anthony. Poetry as Discourse. London and New York: Methuen, 1983.

Eliot, T.S. On Poetry and Poets. New York: Noonday 1957.

Garber, Marjorie. “ “ (Quotation Marks). Critical Inquiry 25 (Summer 1999): 653-679.

Giltrow, Janet. “Vagrant Voices: Summary, Citation, Authority.” Technostyle. 17.1 (2001): 87-103.

Goffman, Erving. Frame Analysis: An essay on the Organization of Experience. New York: Harper, 1974.

Gregory, Elizabeth. Quotation and Modern American Poetry: Imaginary Gardens with Real Toads. Houston: Rice UP, 1995.

Harrington, Joseph. Poetry and the Public: the Social Form of Modern U.S. Poetics. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan UP, 2002.

Huyssen, Andreas. After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture and post Modernism. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1986.

Kluger, Richard and Phyllis Kluger. The Paper: the Life and Death of the New York Herald Tribune. New York: Knopf, 1986.Korda, Michael. Making the List: A Cultural History of the American Bestseller 1900-1999. New York: Barnes and Noble, 2001.

Lawton, Alice. “Alice Duer Miller’s Dual Allegiance”, Boston Evening Transcript, 30 July 1927: Book section, 1.

Lazarus, Emma. “The New Colossus” in Emma Lazarus: Selected Poems and Other Writings. Ed. Gregory Eiselein. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2002: 233.

Miller, Alice Duer. Are Women People? A Book of Rhymes for Suffrage Times. New York: George H. Doran and Co., 1915.

-------- Come out of the Kitchen. New York: Century, 1916.

---------The White Cliffs. New York: Coward-McCann, Inc. 1940.

-------- Women Are People. New York: George Doran and Co., 1917.

Miller, Henry Wise. All Our Lives. New York: Coward-McCann Inc., 1945.

Morrison, Mark. The Public Face of Modernism: Little Magazines, Audiences, and Reception, 1905-1920. Madison: U Wisconsin P, 2001.

Myers, Greg. “Functions of reported speech in group discussions.” Applied Linguistics. (1999) 20(3): 376-401.

“A National Industry” The New Yorker 9 Aug 1941: 10-11.

Nelson, Cary. Repression and Recovery: Modern American Poetry and the Politics of Cultural Memory 1910-1945. Madison: U of Wisconsin P, 1989.

O’Higgins, Harvey. “A Lady Who Writes” The New Yorker 19 Feb. 1917: 25-27.

Overton, Grant. The Women Who Make Our Novels: Freeport: Book for Libraries Press, 1967: 206-213.

“Reviews” [Elyria OH] Evening Telegram 5 Oct 1915: 4.

Schwartz, Judith. Radical Feminists of Heterodoxy: Greenwich Village 1912-1940. Lebanon, NH: New Victoria Publishers, 1982.

Slatin, John M. “‘Advancing Backward in a Circle’: Marianne Moore as (Natural) Historian”. Twentieth-century Literature 30:2 (Summer/Fall 1984): 273-326.

Van Gelder, Robert. “An Interview with Alice Duer Miller”, New York Times Book Review. 29 June 1941. n.p.

Van Wienen, Mark W. Partisans and Poets: The Political Work of American Poetry in the Great War. New York: Cambridge UP, 1997.

Mary Chapman would like to thank Jacqueline Shin and Brook Houglum for their research assistance on this project.

Mary Chapman teaches American literature at the University of British Columbia. She is the co-editor of Sentimental Men: MAsculinity and the Politics of Affect in American Culture (U California P 1999), the editor of an edition of Charles Brockden Brown's novel Ormond (Broadview 1999), and the author of several essays on American literature and culture. This paper marks the beginning of a new project on American suffrage writing and modernist print culture.

Mary Chapman

Department of English

University of British Columbia

Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z1

CANADA