“Nature is a Haunted House—but Art—a House that tries to be haunted”: Los Angeles, Trauma, and Orphic Anxiety in the Work of Jack Spicer

by Alicia Cohen

[Jack Spicer] wondered about his home—a hundred years ago, what had these spaces been? Empty forest, native peoples. It frightened him to think of it, so he tried not to. But sometimes he forced himself to think about it, and that scared him even more. |

—Kevin Killian and Lew Ellingham,

Poet Be Like God

I.

Over the past two decades the psychiatric community has developed an effective but largely inexplicable treatment for trauma called “Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing.” Treatment sessions involve two simultaneous procedures: one, the patient conjures up a vivid picture of his painful experience and recounts it while, two, he focuses his eyes on a therapist’s fingers as she moves them steadily back and forth across his field of vision. Why this procedure works largely remains a mystery, but somehow the dual focus—the gaze of the eyes held steadily when combined with the conjured image of the traumatic event in the imagination—helps to heal the patient’s physical and emotional posttraumatic suffering (Shapiro 199-223).

A puzzling relationship between vision, trauma and healing is embedded in the Orphic myth as well. Orpheus, traumatized by the loss of his beloved, seeks her even to the gates of Hades. Because his poems are so beautiful, he is able to charm his way into Hell—breaking the rules of earth and underworld, life and death. Ultimately, Orpheus is allowed to bring Eurydice out of the Netherworld but on the single condition that he not look at her. Tragically, he cannot resist looking back at his beloved and so loses her again, forever.

It is as an orphic poet that Jack Spicer figured himself from his earliest poems, and it is the project of this essay to explore the relationship of “looking back” to sorrow, trauma and healing in Spicer’s poetry. Spicer’s orphic anxiety about looking back, I argue, is strangely linked to the “vacancy” that he so problematically and relentlessly seeks as an author. An orphic poet, as the Orphée character in Jean Cocteau’s film says, is a vacant subject—“a writer who doesn’t write.” Cocteau’s film seems to have been central to Spicer’s imagination of the orphic, and is indeed the origin of Spicer’s famous poet-as-radio metaphor. Spicer seeks to be a “writer who doesn’t write” and so cultivates a relationship to the self which seeks—at least temporarily—to make the self disappear just as Eurydice disappears when Orpheus looks upon her.

For Spicer, the most difficult work for a poet is not inventing poems but, rather, the labor involved in getting the poet’s own self or ego out of the way so that poems can be effectively channeled from an outside force. In Spicer’s words the poet is, at his best, “a team player” who should seek only to create the ground for the transmission of poem-messages from Others: be they “Martians,” or “God,” or “Ghosts.” In this essay I will explore how the orphic vacancy of the poet’s “self,” so much at the heart of Spicer’s poetic project, can be read in terms of his refusal to “look back” specifically at his own past—to the Los Angeles of his childhood. Spicer’s Los Angeles is a kind of hell, an urban aberration that, he claimed, should not even be considered part of the beautiful California region (Gizzi 243). It is not just his own childhood past in Los Angeles which Spicer refused to talk or write about; even as a child, the very thought of LA’s recent history was deeply frightening to him.

Spicer is typically associated with the Bay Area where he lived most of his adult life. The title of his biography, Jack Spicer and the Berkeley Renaissance, points to this: figuring him as an important player in the art community and locating him geographically in Northern California. Rarely has Spicer been considered in terms of Los Angeles, where he was born and lived until he was twenty years old. Spicer’s biographers Kevin Killian and Lew Ellingham don’t spend more than a couple pages talking about Spicer’s Southern California in their four-hundred page biography. What they do write is that as a child Spicer “wondered about his home […]—a hundred years ago, what had these spaces been? Empty forest, native peoples. It frightened him to think of it, so he tried not to. But sometimes he forced himself to think about it, and that scared him even more” (7). Why should the wide-open spaces that were home to native peoples less than a hundred years earlier, frighten the young Spicer rather than, say, fascinate him? And might these early orphic anxieties about Los Angeles’ past have a role in his mature poetics? Indeed it was as a young boy exploring Los Angeles that Spicer decided to become a poet. His biographers sketch him as a “bookish boy” who loved to investigate:

[He] mastered the Dewey Decimal System while still quite young, and in time became an excellent researcher. He had an innate talent for finding things out. ‘He knew how to use the library in a way that no one I ever met did,’ said a later friend. Jack studied railroad and bus timetables and could really work Los Angeles public transit, [going] on day excursions to the farthest parts of the huge city and its sprawling environs. (5) |

Here, Spicer’s childhood bookishness is linked to his exploration of the physical landscape of LA. But as a writer living in the Bay Area, Spicer refused to return to his native place—he didn’t return to visit nor would he talk about Los Angeles. It was via lies, tall tales, and even silence that Spicer painted a picture of his childhood in LA after he moved to the Bay Area. Many friends thought him an orphan. “He seemed determined to keep his past a secret, to remove even the interest of secrecy from it, so that no one would inquire. […] He made it clear he didn’t appreciate questions about ‘home,’ only ‘California’ ” (8).

By all accounts Spicer’s childhood family life was stable and loving. His parents were kind people—thoughtful political progressives who believed in equality for all struggling people. They raised Spicer and his brother in relative middle class comfort. Still, there are many reasons an adult might not want to look back at their childhood (particularly a gay man in that time)—but why wouldn’t a young boy enjoy imagining a time when his hometown was full of cowboys and Indians? The film genre the “Western” was created in Hollywood, which is the very neighborhood of LA in which Spicer grew up. What was it about the Los Angeles past that Spicer didn’t want to see? Clearly the romances invented and sold à la Hollywood were not effective in silencing or erasing a more sinister and traumatic past for this particular poet.

II. The Haunted House

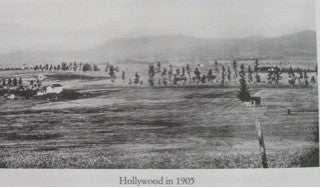

When Spicer was born in Los Angeles on January 30, 1925 it had been only five decades since Mexico lost the village, El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Angeles del Río de Porciúncula, to the expanding United States. In those years the LA basin had transformed into a massive American industrial metropolis.

Hollywood in 1905 (Davis) |

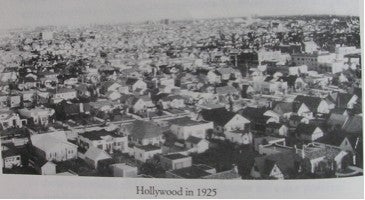

By 1925, the once wide-open forest and costal desert lands populated by the Aboriginal peoples the Tongva and the Chumash were unrecognizable and already suffering hellish consequences from pollution and robber baron land development.

Hollywood in 1925 (Davis) |

In 1943, a couple years before Spicer left for the Bay Area, Los Angeles was already grappling with major environmental catastrophes. Mike Davis writes in his essay “How Eden Lost Its Garden” that “the first smog attack in 1943—an ‘eerie darkness at noon’ over the Los Angeles Basin—caused almost as much consternation as Pearl Harbor” (Davis 166). In the same year the State Board of Health declared a “gross public health hazard” and closed ten miles of fetid beaches to forestall lethal threats of full fledged typhoid and poliomyelitis epidemics” (Davis 166). When the famous Olmsted urban development firm was invited in 1930 to study LA’s already alarming urban sprawl, they recommended a network of urban green spaces that would serve as public parks and as a buffer to natural fire and flood systems, as well as urban traffic congestion. They suggested the arcadian Los Angeles Riverbed area, which regularly flooded, could be turned into a public greenbelt for recreation that would, in times of flooding, serve to absorb the river’s overflow. Tragically, nearly every suggestion made by the Olmsted firm was ignored and the LA River was finally paved over (Davis 161-165). Today the Los Angeles River is an ugly barren channel that looks like a vast cement sewer running through the city. Ralph Cornell, in 1941, at a symposium of the region’s leading architects and planners, lamented: “no other metropolitan center has been so effective…in the obliteration of the natural beauty of its site, in the mutilation of its scenic resources” (Davis 166).

Anyone who has lived for more than a decade in Southern California in the past hundred years knows the sorrow of seeing large areas quickly transformed into sprawling subdivisions, cheap retail centers, or any number of poorly planned, bottom-line oriented, developments. I know it well, having myself grown up in Southern California—coincidentally born on Spicer’s birthday, January 30th, five years after his death. Like Spicer I grew up haunted by the loss which troubles that landscape. Beautiful as it is—and successful as it has been in promoting itself as the home of sunshine and surfing, beautiful people and flashy cars—there is something deeply sorrowful and mournful scratching at the window just at the edge of the social field of vision. It is a landscape that is not simply haunted by ghosts of the past but by a lost world that was erased—wiped out and paved over—in the blink of an historical eye. This strange and grating absence is palpable everywhere despite the lack of historical concern which predominates at every level of social life in the area. It is a place where the history made visible in social spaces and the history taught in schools is, overwhelmingly, either imported from Europe or the East Coast.

When I was growing up our teachers would decorate the walls of our classrooms with symbols of foreign weather patterns: fall leaves in autumn, snowflakes in winter, and tulip bulbs in spring. Only a few imported tree species actually lose their leaves in the fall in Southern California where it is typically sunny and warm even during the winter. It never snowed. Once, in 1976, it hailed enough to partially cover the ground with white for half an hour or so. I was thrilled. On the one hand it pleased me so deeply because it was such a bizarre occurrence but there was a part of me that quite simply felt a joyous relief—I was relieved that my home ecosystem seemed, for once, to have behaved appropriately like the weather in our reading primers, like the snowflakes on our classroom walls. I was not alone; the next day at school half of the kids brought in melting trays of hail which they had collected and kept in their freezers overnight to bring to class and show their teachers and friends.

This is a world that was authored first and then imposed upon the land. When the city that would become Los Angeles was first settled, plans for the pueblo were laid out on paper by men who had never seen the site, based on a report given by missionaries who had visited for less than a full day. The state of California itself is named after a fantastic city rich in treasure from a Spanish romance novel. By 1925, the Aboriginal peoples of Los Angeles and their cultures had been supplanted by others from all over the globe. Many languages—English, Spanish, Chinese, among numerous others—were commonly spoken, though the language and landscape of the Tongva and Chumash had nearly disappeared. Though descendents of the Aboriginal peoples still live in the Los Angeles area today and hold tenaciously to their culture, their presence, unfortunately, is hardly recognized by the culture at large. Both their culture and their valley were in some fundamental sense overwhelmed within a few years of the arrival of the first Americans.

When I was young abalone covered the coastlines; people used abalone shells for ashtrays. Now, only a few decades later, abalone is nearly extinct. There are people still alive who remember when fish the size of small cars cruised the waters close in to shore and shells covered the beaches. The famous Scripps Aquarium in La Jolla loops a brief documentary on the current state of sea-life in Southern California for its visitors called “Ghosts of the Kelp Forest”—and this Spicerian title summarizes the situation fairly well.

While what we are talking about here is not precisely murder (though the descendents of the Tongva and the Chumash might disagree), there is something murderous in the speed and catastrophic nature of violence done in the last hundred years to Southern California. And there is something criminal involved in the complete annihilation of an entire ecosystem—animals, people, flora, and even land and water systems.

However, I am not so much concerned here with labeling the settling of Southern California as a case of murder; rather, I would like to borrow some of the terms of Jean Genet’s analysis of murder in his study of crime, Our Lady of the Flowers. There are many points of coincidence between Spicer and Genet but I am most interested, for the purposes of this essay, in Genet’s novel as it proposes a way of understanding the psychic condition of witnesses to the kind of violence involved in Los Angeles’s recent history. According to Genet’s algebra of violence, the murderer takes the murdered inside himself, where the victim continues to live and the killer’s interior self multiplies:

Your dead man is inside you; mingled with your blood, he flows in your veins, oozes out through your pores, and your heart lives on him, as cemetery flowers sprout from corpses…. He emerges from you through your eyes, your ears, your mouth. (119) |

For Genet, the murder victim does not go to some otherworld (heaven/hell), but stays present in this world as part of the body of the murderer. The murderer is inhabited. The victim is inside of their murderer looking out. The result of murder, then, is the creation of an invisible interiority that is home to multiple “selves.” Genet’s description of the relationship between murderer and victim is direct and personal—but might there be a way of taking Genet’s model of murder and seeing it in a larger social context? Chief Seattle, patriarch of the Duwamish and Suquamish Indians of Puget Sound, up the west coast about a thousand miles north of the Tongva and Chumash, describes a situation of inhabitation similar to Genet in his response to the U.S. President on the occasion of handing over the Northwest tribal lands to the expanding United States in 1854:

And when the last Red Man shall have perished, and the memory of my tribe shall have become a myth among the White Men, these shores will swarm with the invisible dead of my tribe, and when your children's children think themselves alone in the field, the store, the shop, upon the highway, or in the silence of the pathless woods, they will not be alone. […] At night when the streets of your cities and villages are silent and you think them deserted, they will throng with the returning hosts that once filled them and still love this beautiful land. The White Man will never be alone. Let him be just and deal kindly with my people, for the dead are not powerless. Dead, did I say? There is no death, only a change of worlds. (Quoted in Clark, n.pag.) |

This description of a landscape inhabited by the dead shares a vocabulary of haunting and inhabitation with Genet, but particularly with Spicer.1 Spicer’s poetry can be seen as a hybrid of Seattle and Genet with the dead moving both externally and internally around and through the poet. His poetry is a territory in which “the invisible dead” swarm the civic landscape. Perhaps Spicer was afraid to think of his home a hundred years ago, to think of a place that had disappeared as if into a Netherworld, because he was one of those children who when “in the field, the store, the shop, upon the highway, or in the silence of the pathless woods, [was] not […] alone.” Using the Genetian model of murder and inhabitation, I would argue that this impossibility of being alone is not merely felt as an exterior encounter (as in “I think I saw a ghost”), but as an internal condition, troubling the very selfhood of the poet—troubling, certainly, to a contemporary model of the “healthy” psyche: a unified and coherent sense of self, not inhabited by multiple voices.

Despite his insistence that the Others whom he channels have no real concern for nor any message that can be of personal use to the poet, Spicer evolves a poetics centered around a commitment to these voices. He did not consider it his job as poet to make the dead or their past readable or comprehensible to the living. Spicer saw it as his job to provide a channel for the dead to speak, for the Outside to enter.

We can see the strange inversion of world and value which Spicer’s work involves if we compare him to another gay, male, American poet—the iconic Walt Whitman. In Spicer’s prose poem “Some Notes on Whitman for Allen Joyce” from One Night Stand and Other Poems, he describes the gulf between himself and his famous predecessor:

In [Whitman’s] world roads go somewhere and you walk with someone whose hand you can hold. I remember. In my world roads only go up and down and you are lucky if you can hold on to the road or even know that it is there. He never heard spirits whispering or… was frightened by the ghost of something crucified. His world has clouds in it and he loved Indian names… he had no need of death. (81, emphasis mine) |

Whitman’s world may be coherent but Spicer remembers. Particularly striking and odd here is the way “remembering” is linked to spatial regularity. Spicer’s world is not spatially stable like the world we find represented in the poetry of Whitman. In the world of Spicer’s poetry, things do not stay in their proper places. In a spatially stable world, not only does the road one walks have constancy; one doesn’t hear voices calling out from the spirit world as one traverses it, nor suffer the traumas of a dead man’s crucifixion long past. Spicer, as Orphic poet, remembers the death and vertigo of the murdered and disembodied by opening to alien voices not his own. The difference between visible spatial regularity—roads that “go somewhere”—which is found in Whitman, and an unrepresentable world of spatial irregularity—where you are lucky if you can even know the road is there—is the heart of the difference between the poetries of Whitman and Spicer. Whitman’s work is obsessed with gorgeous vistas of an American landscape, and with the vital living bodies of healthy men and women of a democratic polis. Spicer can barely see a thing, but his landscape is loud with invisible voices. He loves too, but without the comfort of laying his eyes upon the beloved’s beautiful, stable form. Only their strange and often incoherent voices are embodied in the language of the poem.

The work of the poet for Spicer, the Orphic poet at least, is brutal work. Spicer always discouraged young people from becoming poets. He did not consider his poetics of the Outside a metaphor for the experience of a writing practice. Poems, according to Spicer, really are received from the Outside. As he says emphatically in his Vancouver lecture:

I think there’s something Outside. I really do believe that, and I haven’t noticed anyone really, in all the people who come here [to my poetics lectures], who did seem to believe that I believed it, but I do. And I don’t care if you don’t. It doesn’t matter a good goddamn to me. But I just want to say for the record that I do believe it. (Gizzi 134) |

This Outside force has no interest or care for the medium. Even their messages are often unreadable by the poet. “No kid don’t enter here,” Spicer claims, is “about the only [message] which is absolutely clear [in the poems] and has told me something about what I should and shouldn’t do in life” (Gizzi 135). And the difference, Spicer writes in his poem “The Sporting Life” from the book Language, between a radio (like the one in Cocteau’s film) and a poet is that “radios don’t develop scar tissue.” In Whitman’s world of the poem, the great bearded bard holds hands with a beloved (muse) and is heading somewhere, whereas Spicer’s beloved (muse) is both practically illegible and someone at whom he is forbidden to look. Spicer walks ahead by himself, coaxing his beloved behind him—not even sure if s/he is there at all—as he struggles with the very road itself which is all vertigo and illusion, shifting, and shape shifters.

In Cocteau’s film, the passageway to and from the Netherworld is through mirrors. One of the last lines of “Some Notes on Whitman” also refers to mirrors as a passageway between worlds: “And one needs no Virgil but an Alice, a Dorothy […] to lead one across that cuntlike mirror, that cruelty” (81-82). For the purposes of this short essay I won’t go into the obvious, potent, and crass birth imagery here. Instead, I will focus briefly on Jacques Lacan’s reading of mirrors in his essay delivered in 1949, titled “The mirror stage as formative of the function of the I as revealed in psychoanalytic experience.” Lacan’s essay suggests a way of reading the significance of the mirror (which is an important figure throughout both Spicer’s poetry and in Cocteau’s Orphée) as it is related to the vacancy of the Orphic author, the poet-as-radio.

Lacan, like Spicer, was centrally interested in the way language forms both our subjectivity and our sense of the “real.” For Lacan the territory of language, or the “symbolic order,” forever obfuscates the Real. He argues we cannot precisely speak of the Real because we speak in language which skews not just descriptions of the Real but—because the “symbolic order” fundamentally participates in the creation of our vision of the world—even the possibility of seeing the Real. In other words, how we think (in symbols) determines how and what we see. Despite the centrality of language in the construction of the “real,” according to Lacan, the induction into the “symbolic order” begins not with the human child’s first words but rather in front of a mirror.

At around the age of six months the human infant becomes capable of recognizing her reflection in the mirror. This is not a capacity unique to humans; chimpanzees from this same age can recognize their image in a mirror. However, according to Lacan, humans and chimpanzees differ in one key way:

[The reflection], far from exhausting itself, as in the case of the monkey, once the image has been mastered and found empty, immediately rebounds in the case of the child in a series of gestures in which he experiences in play the relation between the movements assumed in the image and the reflected environment, and between this virtual complex and the reality it reduplicates — the child's own body, and the persons and things around him. (1) |

The chimpanzee becomes bored once she realizes that her image is nothing more than an empty reflection and not another chimp. The human child, however, will never cease to be fascinated by her self-reflection. Indeed, seeing the self in the mirror is the start of a life long love affair with the visible self. This obsession with the reflected self is tightly bound up with the child’s construction of both spatial and temporal/historical location which also evolves by way of the mirror stage:

[T]he function of the mirror-stage […] is to establish a relation between the organism and its reality—or, as they say, between the Innenwelt [interior world] and the Umwelt [exterior world]. […] This development is experienced as a temporal dialectic that decisively projects the formation of the individual into history. The mirror stage is a drama whose internal thrust […] manufactures for the subject, caught up in the lure of spatial identification, the succession of phantasies that extends from a fragmented body-image to a form of its totality […] —and, lastly, to the assumption of the armour of an alienating identity, which will mark with its rigid structure the subject's entire mental development. (4) |

The mechanics of desire, sense of self, and allegiance to the “symbolic order” all have their first flowering in front of the mirror. The mirror is the canvas upon which we experiment with reality and, finally, through which we are inducted into the “phallic order.” We long for the visible phantom self who is reflected so seductively in the mirror and that longing drives the creation of ego. And finally, this longing for unification of self serves as the primary tool of phallic culture to coerce capitulation.

Though the self/world in the mirror is a mere reflection, it appears from an internal vantage more “real” than the world experienced directly. The internal world of the self is fragmented and confusing; whereas the reflected image of the self and the world in which it is spatially located appears whole, unified, and coherent. It is through the fantastical processes of imagination that we are able to fashion an internal self to match the external image of self seen in the mirror. We desire the mirrored self and seek to follow it, to leave behind the absurdities of our internal confusions and desires. The self in the mirror is something like the world Walt Whitman reflects in his poetry—lovable, stable, having purpose. Whereas the invisible, unreflected experience of self is more like Spicer’s—it is the rabbit hole underworld of Alice in Wonderland or Dorothy in the Land of Oz— a landscape of confusion and uncertainty in which Spicer locates himself.

The idea that there is a coherent subject inside each of us that can see the world and know it (the Cogito), serves not only as the root of authority’s power over us, but also to banish the multiple voices/selves that inhabit our being. Spicer in his poetry and poetics figures the self as a formidable figment of the imagination become actual. The self is an impediment that when displaced (a very dangerous business) clears a channel for other selves/souls/beings to move through. As Emily Dickinson says in her famous letter: “Nature is a haunted house, poetry a house that tries to be haunted” (236). The work of the poet is to try to be haunted—to write a poem in which the dead can speak. Spicer makes clear, perhaps more vividly than any other American poet, one must “try” very hard, and the stakes are extremely high. As he says on his deathbed (Spicer died when he was only forty years old, but was mistaken by the hospital staff for an old man): “my vocabulary did this to me.” To create the ground for such haunting is both frightening and dangerous.

III. Conclusion

So why not look back? Why did Spicer refuse to look back at Los Angeles? To suffer trauma is to fracture, fragment, and lose control of the self. To look with desire at the beloved is, within the libidinal economy of the mirror, the means through which we maintain a unified sense of self free from trauma and confusion. It is this internal fragmentation EMDR therapy seeks to reverse by literally looking at the trauma—holding the gaze of the eye, while reliving the world-shattering event in words, in the imagination.

Perhaps, for Orpheus as trauma sufferer, looking back at Eurydice was not an act of love for her but rather a way for the poet himself to return to a coherent upper world free from the traumas and absurdities of hell. What distinguishes Spicer from the Orpheus of mythology or Orphée in Cocteau’s film is that he never looks back. If Orpheus’s glance at Eurydice meant a certain “healing” at her expense, then what would it have meant if he had not looked back? Perhaps Spicer refuses to look back not because he despised Los Angeles, but because he loved it well. Not just the LA of his childhood but the lost LA—the world and its inhabitants that were buried to make way for the dream of manifest destiny, an American metropolis on the Pacific. Spicer writes, “Forgive me Walt Whitman, you […] never did understand cruelty. It was that that severed your world from me, fouled your moon, and your ocean, threw me out of your bearded paradise” (81). By seeking to undermine the stable world constructed during the mirror stage, Spicer makes a passageway for the inhabitants of the lost Los Angeles to, like Eurydice, come up into the civic landscape.

America is a democracy where even the common man or woman supposedly has a vote—but what of the voiceless? The “insane”? The dead? In his work, Jack Spicer troubles the democratic vista by creating virtual spaces where these disembodied Others, these non-coherent, non-unified beings, emerge to trouble and participate in the “real.”

Notes

[1] - For a detailed history of the origins of this speech see Jerry Clark’s excellent essay “Thus Spoke Chief Seattle: The Story of An Undocumented Speech” in Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration, Spring 1985, Vol. 18, No. 1. (Back to text)

Bibliography

Clark, Jerry L. "Thus Spoke Chief Seattle: The Story of An Undocumented Speech." Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration Vol. 18 (1985).

Davis, Mike. “How Eden Lost Its Garden: A Political History of the Los Angeles Landscape.” The City: Los Angeles and Urban Theory at the End of the Twentieth Century. Ed. Allen Scott and Edward Soja. Berekely: University of California Press, 1966.

Dickinson, Emily. Emily Dickinson: Selected Letters. Ed. T. H. Johnson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958.

Killian, Kevin and Lew Ellingham. Poet Be Like God: Jack Spicer and the San Francisco Renaissance. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1998.

Lacan, Jaques. Écrits: A Selection. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Norton, 1977.

Shapiro, F. “Efficacy of the eye movement desensitization procedure in the treatment of traumatic memories.” Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2 (1989) 199-223.

Spicer, Jack. One Night Stand and Other Poems. Ed. Donald Allen. San Francisco: Grey Fox Press, 1980.

Spicer, Jack. The House That Jack Built: The Collected Lectures of Jack Spicer. Ed. Peter Gizzi. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 1998.

Alicia Cohen lives in Portland, Oregon, where, in 2000, she helped establish the art space collective Pacific Switchboard. She has published a book of poems, bEAR, with Handwritten Press and last year wrote, directed, and produced a multimedia opera and gallery installation for the Core Sample exhibition titled Northwest Inhabitation Log. She earned her doctorate at the University of New York, Buffalo, writing a dissertation on vision and epistemology in the work of Jack Spicer, Emily Dickinson, Leslie Scalapino, and Robert Duncan. Her poetry has recently appeared in Ecopoetics, BirdDog and Traverse. She is poetry editor for the Organ Review of Arts.