Granary Books

Jen Bervin

For over a decade, publisher Steven Clay has taken an unprogrammatic, organic approach with Granary Books, intuitively following his interests as they have developed in the areas where experimental poetry, art, music, and bookmaking overlap.

In its earliest incarnation in Minnesota, Granary was primarily a distributor of literature printed in fine editions. When Clay relocated to New York City’s Soho in 1989, it became a gallery specializing in artists’ books. Clay cites his decision to move to New York as central to Granary’s early development as a press. Being in New York allowed him to meet writers and artists in the community easily, to bump into them frequently, and to be introduced to visiting writers who filtered through town. During the early nineties, the gallery exhibited some of the first artist’s books Granary published—among them John Cage’s Nods, a book Clay cites as a turning point for his intentional entry into publishing. He had published occasional broadsides, show invitations, and a handful of books prior to that, but the efforts were more spontaneous and singular. By 1995, Clay gave up the gallery space in favor of publishing.

Granary’s office is quietly nestled high above Seventh Avenue in Chelsea. Visiting the press feels a good deal like stopping by any writer’s apartment. It’s packed with books. Floor to ceiling shelves house Granary's collection; the remaining space is heaped with piles of incoming and outgoing books. It’s an inviting muddle, a little dizzying at times. There’s a lot to take in besides the smorgasbord of books—like the stunning little Barbara Fahrner drawings which lie discreetly in a glass case. Additionally, authors filter through—Larry Fagin leaves, Jerry and Diane Rothenberg drop some things off—a prospective intern interviews. Yet even in the midst of what appears to be a very busy day, publisher Steven Clay and publicist/promotions person Jo Ann Wasserman generously take the time to sit down to discuss the press.

In just one decade, Clay has published over eighty poets and artists, many repeatedly—Johanna Drucker, Barbara Fahrner, Lyn Hejinian, Jerome Rothenberg, Charles Bernstein, Susan Bee, Robert Creeley, Ed Epping, Anne Waldman, and Lewis Warsh have all been involved in three or more projects. Clay has worked with art curators, co-edited books with Jerome Rothenberg and Rodney Phillips, and has presented many more edited by others—Jay Sanders and Charles Bernstein’s Poetry Plastique, John Zorn's Arcana: Musicians on Music, Anne Waldman and Lewis Warsh’s Angel Hair Sleeps with a Boy in my Head: The Angel Hair Anthology, to name a few. Clay uses phrases like “family affinities” to capture the underlying resemblances of Granary’s ouvre. He and Jo Ann Wasserman joke about the Press’s one hundred children, “some adopted, some milkmen’s bastards, some with multiple biological parents.”

Visually, Granary books are varied and unique; they don’t have a unifying “look.” “I didn’t want it to all fall into line,” Clay says. Granary places the emphasis on the total work, on every aspect of the construction—the quality of the paper, the binding method, the typography, printmaking, size, shape—and how it responds to the qualities of the writing. The book is not simply a “neutral container,” Clay says, “but something that plays a semantic role.”

Granary doesn’t accept unsolicited manuscripts; in most cases, Clay extends invitations to the writers he is interested in working with. He prefers to be “an animating force” in suggesting a project, especially the collaborative limited editions. Sometimes the projects are already in progress when Clay adopts them; such was the case with

|

|

Figs. Excerpts from The Traveler and the Hill and the Hill

The Traveler and the Hill and the Hill. Clay knew he wanted to do a book with Lyn Hejinian even before he learned that she and painter Emilie Clarke were already at work on a collaboration. He loved the work in progress, published the book, and offered to release their next collaboration, The Lake.

In other scenarios, the writers may have been collaborating for decades, as was the case with Jerome Rothenberg and Ian Tyson. Or prior Granary writers might resurface in a new collaboration. With Rosmarie Waldrop’s first Granary book, Clay invited her to select anyone at all as her collaborator. She chose to translate Edmund Jabés’ Desire for a Beginning Dread of One Single End as a collaboration with another Granary artist, Ed Epping. “So it just kind of moves around,” Clay explains. Jo Ann throws in: “Like an old time studio!” (At this point who says what blurs in laughter) “We have our stable of actors... Ed Epping as a tall Mickey Rooney...”

Granary’s editorial operations may be centered in New York, but not its sales. The staff travels far and wide to sell books, visiting special collections libraries and hosting booths at fairs. Granary Books are available on-line through their website, and are distributed to bookstores by D.A.P. (Distributed Art Publishers) in New York City and Small Press Distribution in California.

When asked if it’s difficult to find buyers for the limited edition books, Clay laughs and replies: “The $20 dollar books need buyers too! It seems like the cut-off for whether people will or won’t buy a book is around twelve dollars. It’s easier to sell a $3,000 book than one costing $30.”

Basically all of the trade books—the paperbacks—don’t offer much of a financial return. A book like Angel Hair has about 620 pages of poetry to edit. A run of 1500 costs $35,000 to produce and retails for $28.95 a piece. The first order from Granary’s distributor (to satisfy all orders world-wide) was for 250 paperbacks and 40 hardback books. From this, the Press gets paid about 30 percent of the retail price by its distributor—four months after the order is placed.

|

|

“But many things just seem to need to be done,” Clay says. Whether it’s a case of returning something to print, like the work contained in Waldman and Warsh’s The Angel Hair Anthology, or making an entire critical apparatus available like Jerome Rothenberg and Steven Clay’s A Book of the Book, these works support the larger project of becoming more accessible to more people. Granary has been filling a need in a number of communities lacking significant histories in print: including artists’ books, small press publishing, and experimental music. Rather than publishing books and then seeking an audience, Clay has recognized audiences in need of books, as was the case with Johanna Drucker’s A Century of Artist’s Books. One thing has truly led to another at Granary, with each book stimulating numerous ensuing projects.

In making a trade book, the Press is more engaged in the total process than with a collaborative artists’ book. More work is done in-house: looking at proofs, seeing the design through multiple stages. Granary’s art director Julie Harrison plays a vital role behind the scenes; she is directly involved at nearly every level of a project. (She has also done two books with Granary: If It Rained Here with Joe Elliot and Debtor's Prison with Lewis Warsh.) Additionally, the trade books often lend themselves a public event involving community outreach. As Wasserman adds, “It brings it to the people.”

Artists’ books require a one-on-one experience; they also usually require much less editing by the Press—maybe one long poem, maybe ten poems. And it’s more lucrative financially. For example, Lyn Hejinian and Emilie Clark’s The Traveler cost $25,000 to make. The letterpress and the binding work was done out of house. Emilie Clark painstakingly printed all of the monotypes—in every single book—herself. The sumptuous finished edition retails for $3,000. Granary easily sells ten books in the first two weeks to university libraries and special collections, more than covering the full cost of production immediately. After production expenses have been paid, Clay splits the profits generously between the collaborating artist and writer and the Press.

Clay also supports Granary through his work as a dealer in archives, manuscripts, and rare books. Sometimes it’s an obvious placement, like selling Burning Deck Press’s archive to Brown University in its own hometown. But often it’s a more tailored relationship; Clay recently helped place the literary archives of Charles Bernstein, Kathleen Fraser, and Kenward Elmslie in the Mandeville Special Collections Library at the University of California, San Diego. Although Clay works with many individual and institutional collections, he says he especially appreciates the Mandeville because it is very accessible and the archives retain “a sense of family” next to those of poets George and Mary Oppen, Charles Reznikoff, Jackson Mac Low, Jerome Rothenberg, Hannah Weiner, Lyn Hejinian, and others.

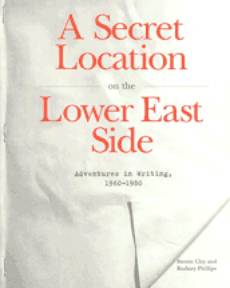

Preservation is one of the issues Granary focuses on in the poetry community, helping work find homes in permanent collections. But their work gathering rare and out of print poetry lineages for readers at large has been one of the Press’s finest contributions. A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing, 1960-1980 documents two decades of the hard-to-trace history of small press publishing and mimeographed magazines. It allows a reader to glimpse what a huge variety of journals and publications looked like, to learn who edited them, where they were made, and how long they were active. A Secret Location demonstrates how the small publishing efforts shaped the poetry of the 60’s, 70’s, and 80’s and shows what kind of relationships some of the different schools of poetic thought—the Black Mountain School, the New York School, the Beats—had in print. It’s a valuable history for poets and scholars and an inspiring model for future editors and publishers; it shows how potent small-scale efforts can be.

“These presses and this poetry have been my passion for twenty years,” Clay explains. “I had already done a lot of the legwork for A Secret Location.” Similarly, co-editor Rodney Phillips, curator of the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library, watched all of those publications come into the collection as they were produced. (Ironically, the Library’s policy at that time was to microfiche and then throw away the originals, a loss Phillips has been rectifying ever since, buying up originals as they become available and demonstrating—as Clay stresses—that “there is something in the artifact.”) When it came to the monumental task of researching and writing, Clay and Phillips “just divided it up,” drawing on their own knowledge, conducting interviews, gathering existing documentation, and using the project as an occasion to invite many editors of the less traceable publications, like Lyn Hejinian's Tuumba, to write their own histories.

|

|

Over the last decade, the Internet has made access to even the most obscure poetry presses much simpler, but tracking down Granary’s out-of-print books or the rare limited editions requires a more concerted effort from the average reader. Complete collections of Granary Books can be found on the West Coast at Stanford, the Getty in L.A., and the Mandeville in San Diego (nearly complete); at the University of Iowa in the Midwest; and on the East Coast at the University of Delaware, Yale, the Library of Congress, and the New York Public Library. These collections are all available to the public by appointment.

Additionally, a recent Granary publication, When will the book be done? gives a rich visual overview of the Press’s books, broadsides, cards, and catalogues to date and is accompanied by bibliographic description and commentary from authors, editors, and critics. The book is part of a larger effort to gain more visibility for the press.

Realizing that it’s difficult to broaden Granary’s audience through what sometimes feel like narrow channels, Clay and Wasserman are looking for new ways to promote Granary and the wider intersection of art and poetry, past and present. “Publishing is a big part of what Granary does, but not all,” Wasserman says. Using the model of A Secret Location for large-scale curatorial projects, they are focusing on broader domains, considering ideas for accompanying exhibitions, catalogues, even tours—orchestrating a sort of “moveable feast.” Beyond that, in his typically fluid approach, Steven Clay hopes to pursue the opportunity to work off of “whatever may come out of it all.”

Bio:Jen Bervin, poet and visual artist, lives in Brooklyn. She is the author of under what is not under (Potes & Poets 2001) and numerous artists’ books. Her work has been published in Chain and Insurance Magazine; is also viewable online in How2’s archives at http://www.scc.rutgers.edu/however/v1_3_2000/bervin/index.html. She and Alystyre Julian are currently collaborating on cloud poems; their work in progress is on view in Poets & Poems: http://www.poetryproject.com/bervin.julian.html. Bervin received a BFA in Studio Art from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and an MA in Poetry from the University of Denver. She currently teaches poetry at NYU’s School of Continuing and Professional Studies and bakes pies at Bubby’s Pie Co. in Tribeca.