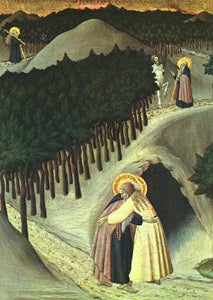

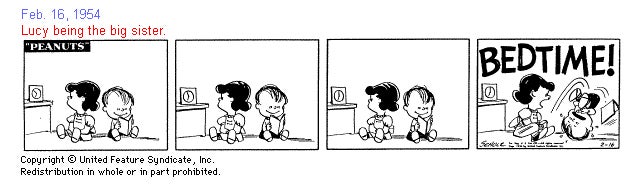

There are many ways to tell a story visually with traditional media--including of course the familiar multi-panel "cartoon." But many other formats are available including scrolls, calendars, road signs (e.g., sequenced Burma Shave signs), "before and after" photos, diaries and other variations on the book. Sassetta (Stefano di Giovanni), provides a compelling visual narrative in his painting, The Meeting of Saint Anthony and Saint Paul (c. 1440). Three moments or "frames" from the story of the two saints meeting are positioned along a winding road in a single landscape. Cartoonists such as Charles Schulz, the creator of Peanuts, and others have long favored the familiar four paneled layout. In the example below, the story unfolds wordlessly as Lucy focuses her attention on the hands of a tiny clock that inches towards the time of 7 PM over three of the four panels,prolonging the suspense. At the stroke of the hour, she screams at Linus, her baby brother,"Bedtime!"

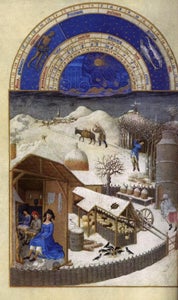

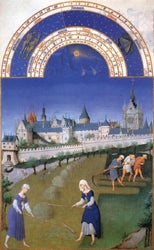

A very different approach to the idea of the "multi-panel" work is the collection of famous prayer books by the early 15th century French artists, the Limbourg Brothers. Each panel of these illuminated manuscripts represents a month from the calendar year and depicts scenes appropriate to the changing seasons.

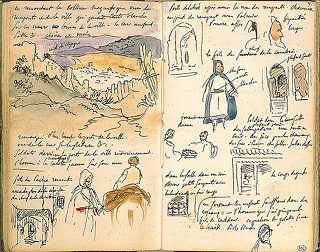

Travel diaries and journals are often sequenced chronologically and provide rich insights into the lives of artists. The Romantic French painter, Eugène Delacroix, in traveling to Morocco in the early 19th century, kept a diary of his travels--a wonderful blend of drawing and text. Eugène Delacroix, Moroccan Notebook, 1832.

Generally, to register time, there needs to be some indication of motion or a perceived change in state. "Before and after" images tell a "wordless" story in multiple panels using the latter means. For example, the paired images from advertisements for weight loss or reconstructive surgery indicate significant changes in the appearance of an individual that imply not only physical transformation, but also the passage of time. Normally, the desired change (say, weight loss) is indicated as a logical sequence of two images where the left image (the side that Westerners begin reading)indicates the past and the image on the right indicates the present.

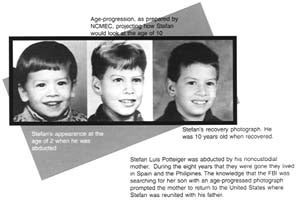

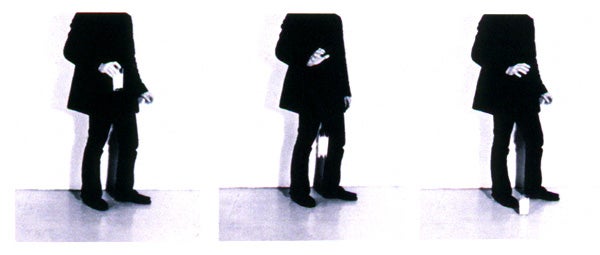

Somewhat more complex are sets of images that indicate possible futures. The mass mailings imploring "Have You Seen Me?" often show an image of a child or young adult--taken the last time they were seen--with the computer-generated image of how they might appear today and in the future. The three images below were created using standard predictive measures of how a human face ages over time. Loss of baby fat, elongation of features, deepening of the lines of the face, change of hair style, familial genetic traits, etc. are taken into account by the forensic artist. http://www.missingkids.com/html/ageprogession.html While the above two examples represent a certain inherent "logic" in the relationship of images that suggest the passage of time, some artists have capitalized on our tendency to expect images that logically follow when "reading" from left to right. William Wegman, for example, in his photographic series, Dropping Milk, subverts our expectations of a logical outcome. Three images in sequence undermine what we know to be "true" about the physical laws that govern falling objects.

William Wegman, Dropping Milk, 1970.

|

||||||||||||